Ryan Mosley’s paintings depict vividly coloured and multi-layered worlds that are fantastical and hallucinatory, inhabited by imaginary, peculiar figures. They are bearded, afro-headed, or hatted, can be genderambiguous or zoomorphic, and are dressed in eccentric outfits that transcend all trends in fashion. Appearing on the canvas either as part of a scene, or alone as a portrait, they evolve and dissolve and balance between representation and delusion.

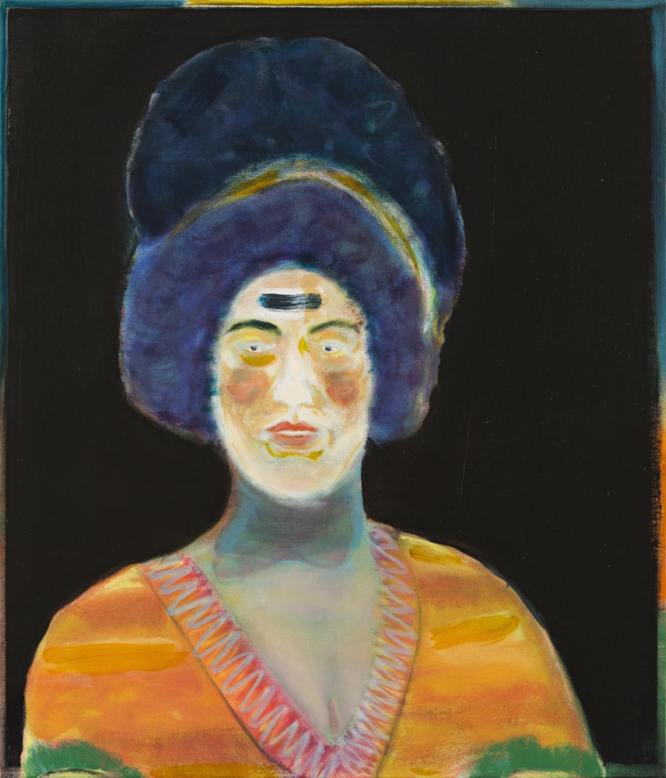

In Mosley’s scenes the characters engage in an array of activities, such as dancing, playing an instrument, or simply conversing. There often is an allusion to performance and theatre, emphasised by the subtle presence of a stage or audience, where recurring props vary from cacti to snakes, birds and leafy natural shapes. In his portraits, Mosley depicts fictional characters with traits similar to the figures in his scene-like paintings. Beards can be blue, skins green, and blushes as orange as mandarins. The portrayed figures match or even blend in with their as vibrantly coloured, and often patterned, backgrounds.

In Oracle, the subject has a cloudy black afro that is so substantial in size that it can only but drift off the picture plane, conveying the oracle’s large personality as well as functioning as a weighty visual anchor. The white daubs on either sides of the woman, and the purple smudge on her neck, symbolise the nature of the material in which she is constructed. At the same time, they evoke depth by breaking the flatness of the plane. This motif of the daubs reoccurs in An Oracle’s Vision, this time as a firm painterly mark on the woman’s forehead. Besides its formal purpose, the mark may suggest a narrative.

Speculation is encouraged by the woman’s gaze: fixed and without making contact with the viewer. Is she in a trance or meditative concentration, receiving a vision? Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery’s collection contains a strong seam of portraiture, dating back to the work of Plymouth’s native Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792). In recent years, Plymouth has begun to augment its collection with contemporary works that question what a portrait constitutes. The addition of Oracle and An Oracle’s Vision is therefore a vital step towards further development of this particular area. As the figures are imagined, and there are hints of narratives but no story, they also form an excellent parallel to Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s portrait To Tell Them Where It’s Got To (2013), acquired in 2013 with the support of the Contemporary Art Society.