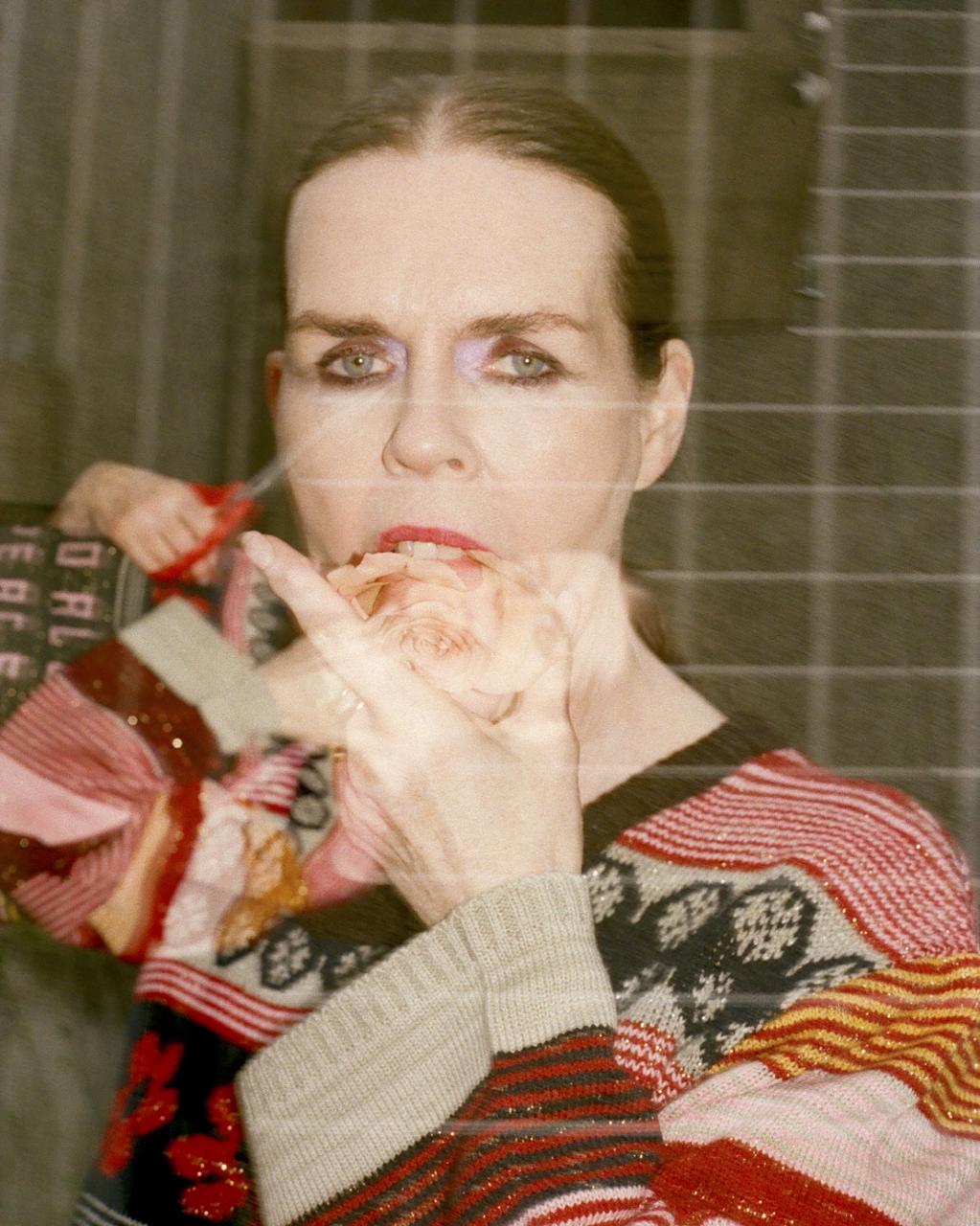

Linder at the Hayward Gallery. Photo: Hazel Gaskin. Outfit: Ashish. Make-up: Kristina Ralph Andrews. Courtesy of the artist; Modern Art, London; BLUM, Los Angeles, Tokyo, New York; Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm, Paris and dépendance, Brussels

Linder: Danger Came Smiling

Hayward Gallery

In 1982, the Manchester-based band Ludus released their first album Danger Came Smiling. A title selected by the band’s frontwoman Linder Sterling, it was a tongue-in-cheek reference to the Mills & Boon-type romantic novels found in the home of the singer’s grandmother. Now known simply as ‘Linder’, she is primarily recognised as a visual artist before a musician. Yet in the spirit of her northern post-punk origins, Linder has never lost her rebellious and irreverent streak. In honour of her career, the artist’s first London retrospective at Hayward Gallery, aptly titled Linder: Danger Came Smiling, assembles over five decades of work, shining a light on the evolution of her practice.

Born in Liverpool in 1954, Linder came of age in the climate of post-war Britain. It was a time of youth dissatisfaction, labour strikes, and an anarchic spirit, all of which fed into the underground music scene of the north with the arrival of the Sex Pistols, the Buzzcocks and Roxy Music to name a few. Linder studied graphic design at Manchester Polytechnic in the mid-1970s, where she encountered the work of the German Dadaist Hannah Höch and read books such as Dawn Adès’ Photomontage, which traced the avant-garde history of photomontage. Whereas Höch fragmented and spliced imagery from political newspapers to satirise life in Germany’s Weimar Republic, Linder turned to her own epoch – the boom of mass media and consumer culture, particularly fashion magazines, pornography and advertising. This early interest culminated in her series Pretty Girls from 1977.

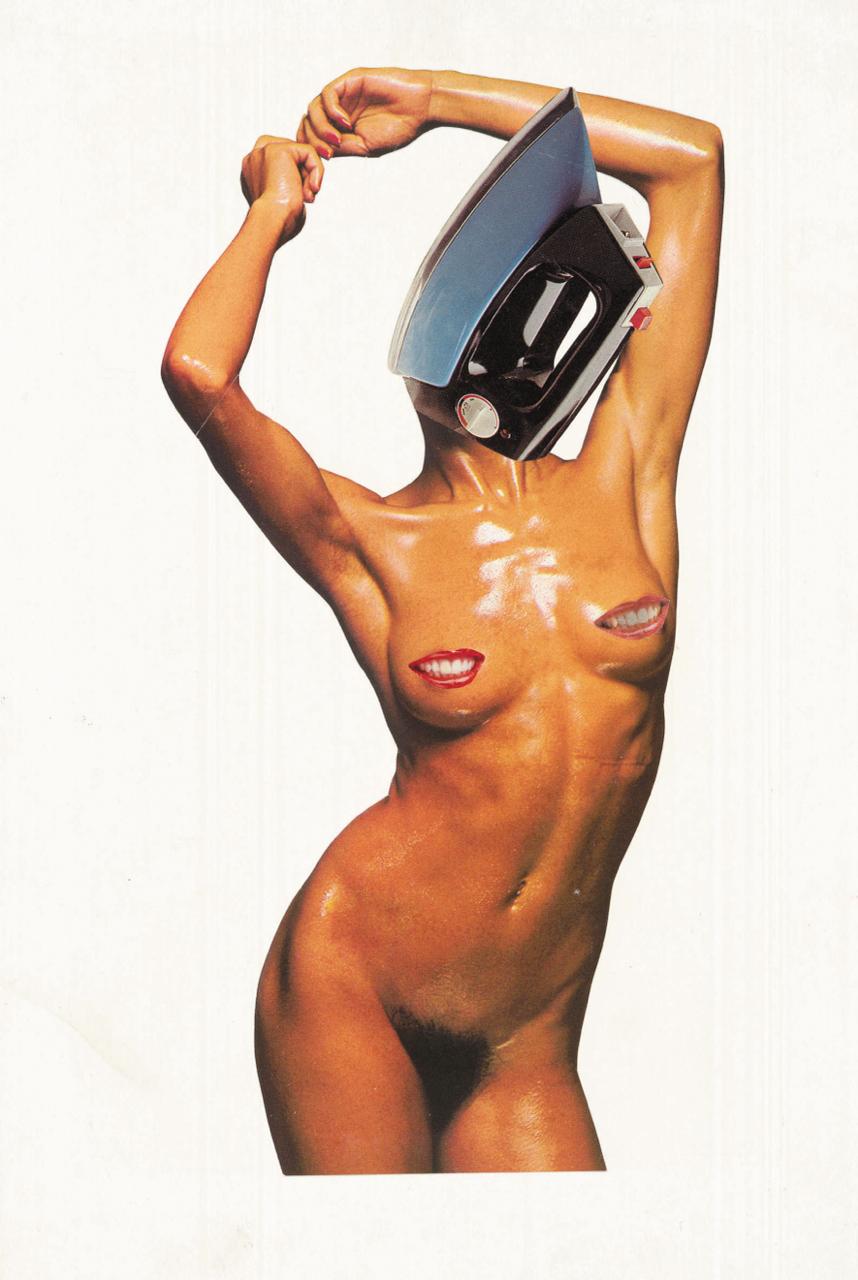

Untitled, Linder, 1976. Tate, purchased 2007. ©️ Linder. Photo: Tate

Upon entering the Hayward show, we are immediately introduced to one of her most iconic images following the Pretty Girls series – Untitled 1976. The work reveals a tanned, oiled-up, naked woman's body. The image would later be used for the record sleeve of Buzzcock's single ‘Orgasm Addict.’ The figure is slender and seductive. Yet in Linder’s playful reinvention, the model’s head is replaced with an iron; her nipples covered with smiling, rouged mouths. Reminiscent of the works of the Austrian artist Birgit Jürgenssen, who toyed with images of the housewife stereotype (her female figures are subsumed by kitchen appliances), Linder’s work similarly probes notions of domesticity and sexuality through a distinctively satirical and feminist gaze. The power lies in the disturbing ambivalence of the image. Linder provokes but doesn’t preach. Instead, she appropriates, exploits and undermines the male gaze – with a dangerous and seductive smile like those adorning the torso of the female figure.

Linder is proudly a feminist. Many of her earliest photomontages were informed by the radical texts of second wave feminism from the 1970s. In particular, the writings of Germaine Greer, Kate Millett and Shulamith Firestone. In 1982, the same year she released her first Ludus album, Linder dressed in raw meat at a concert at the Hacienda nightclub in Manchester – a sartorial statement that would later be echoed by Lady Gaga’s famous meat dress at the VMAs in 2010. Constructed from discarded entrails she sourced from a local restaurant, Linder staged the performance as a protest against sexism within the punk scene. As Marina Warner highlights in the exhibition catalogue, the very name of the band Ludus (“giving an ironic nod” to the word ludicrous) announced its position as an audacious, transgressive musical group. And Linder proposed a more feminist variety of punk.

Installation view of Linder: Danger Came Smiling. Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery.

Although Linder’s appropriation of pornographic and fashion imagery plays into the feminist discussions of the era, it also alludes to early childhood traumas. She has spoken courageously and openly about sexual abuse at the hands of her grandfather, who would often show her his stash of porn mags or gift her musical instruments as a pretext to initiate other forms of nefarious behaviour. In this sense, Linder’s iconoclastic act of cutting up images can be read as a kind of personal expunging, or working through such early experiences. But on a universal level, the gesture also responds to societal objectification and violence towards women’s bodies, particularly during that era. The act of fragmenting images – constructing and deconstructing – mirrors her own psychology. “If I am in a positive mood, I’m interested in joining,” Linder explained, as she discussed her artistic process. “If I am in a negative mood, I will cut things.”

Throughout the Hayward show, we are introduced to contrasting bodies of work, revealing her willingness to experiment with other mediums, including photography, textiles, sculpture and installation. In the centre of one room, her spellbinding, serpentine, multi-coloured rug, Diagrams of Love: Marriage of Eyes, 2016, cascades onto the floor. A collaboration with Dovecot Studios, the rug was created for a ballet conceived by Linder, titled Children of the Mantic Stain, a double entendre on the expression ‘cutting the rug’, it also referred to a landmark essay written by the Surrealist artist Ithell Colquhoun. The Surrealist notion of the uncanny object is pronounced in Linder’s practice, most notably in one particular work featured in the Hayward show, L’effet de la curiosité feminine, 2023, in which locks of blonde hair hang from a glass bell jar containing gold-leaf lacquer regalia. Disturbing and disquieting, the sculpture recalls the disembodied objects of Méret Oppenheim.

Installation view of Linder: Danger Came Smiling. Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery.

Like her avant-garde predecessors, particularly those affiliated with Dada and Surrealism, Linder reinvigorates the tradition of politicised photomontage. She combines juxtaposing imagery that serves to shock, beguile and electrify. By doing so, she invites us into a glamorous yet confronting world where we are invited to laugh at the absurdity of our normalised surroundings, most notably, the divisive, sexual politics surrounding representations of women.

As implied by the title, Danger came smiling, Linder’s art has a subtext. It points to the insidious visuals of consumer culture, which often deploys artifice to distract and desensitise. In homage to the spirit of punk, Linder loudly jolts us into reality.

Lydia Figes, Curator of Digital

Linder: Danger Came Smiling at Hayward Gallery

11th Feb – 5th May 2025