Alice Neel, David and Catherine Saalfield, 192, oil on canvas © The Estate of Alice Neel Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel, David Zwirner and Victoria Miro

Victoria Miro, London

30 January–8 March 2025

Two years after the Barbican’s expansive retrospective, the show at Victoria Miro’s Wharf Road space arrives in the UK after a hugely well-received debut at David Zwirner in Los Angeles. Curated by the renowned writer, academic and native New Yorker, Hilton Als, the exhibition accentuates Alice Neel’s immersion in the intellectual, queer community of her time. In describing his selection, Als notes that it is ‘not just portraits of gay people but those of theorists, activists, politicians, and so on who would qualify as queer by virtue of their different take in their given field and thus the world. So doing, they reflect Alice’s own interest in and commitment to difference.’

Having grown up in a lower-middle class family in Pennsylvania, as a young woman Neel always knew she wanted to be an artist. In an era that offered few opportunities for women, and with little encouragement from her parents, she nevertheless went to study at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. At the age of 25, Neel married the Cuban painter Carlos Enriquez. The young couple promptly moved to Cuba where they remained until 1927. Although Enriquez was from a wealthy family and the two lived in relative comfort, it was in Havana where Neel developed a political sensibility that would forever shape her life and work. Despite personal tragedies that unfolded throughout the 1920s, which subsequently led to a breakdown, Neel never ceased to paint. In 1931, she was released from a psychiatric hospital and moved to Greenwich Village, where due to living in proximity to marginalised and impoverished communities, Neel’s portraiture – informed by her burgeoning socialist politics – began to show a deep psychological empathy and connection to those she encountered.

Installation view, At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World, © The Estate of Alice Neel Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel, David Zwirner, and Victoria Miro

The earliest work in the current exhibition dates from 1932 and is a portrait of Martin Jay, a poet and prominent figure in the Communist party. In its symmetry and stillness, depicting his hands clasped and thumbs pressed together, it holds all the intensity of Neel’s later portraits. The gaze of the sitter, diverted to one side, expresses introspection, but there is also a sense that this young man is offering himself up to Neel. The painting speaks to the mutual trust between artist and model, a characteristic of her work that would define Neel as one of the greatest American portraitists of the 20th century.

In 1938, Neel departed Greenwich Village and moved to Spanish Harlem, an ethnically diverse neighbourhood she formed a deep attachment to and that would influence her choice of subject matter. For example, her painting Ballet Dancer of 1950 compresses the lithe figure of a dark-skinned, young man into the narrow, horizontal canvas – yet his confidence in his own power and agility is vividly tangible through cranked limbs that nudge at the edges of the frame.

Installation view, At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World, © The Estate of Alice Neel Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel, David Zwirner, and Victoria Miro

On the upper floor of the gallery, two startlingly different portraits hang side by side: a 1960 work of the poet Frank O’Hara and a 1979 portrayal of John Cheim, who would later establish the gallery Cheim and Reid. O’Hara is gaunt, with liver spots covering his high forehead. Apparently captured in mid-conversation, his mouth is ajar, revealing a highly un-American dentition. His arm is hooked around the back of the chair and his fingers seem to drum nervously on the seat. The leader of the New York School of poets and associate curator at the Museum of Modern Art, O’Hara worked on numerous exhibitions, including The New American Painting which introduced European audiences to Abstract Expressionism in the late 1950s, and has been subject to recurring conspiracy theories ever since. Cheim, in total contrast, is all glossy curls, broad shoulders and full lips. He gazes directly at the artist painting him, alert, interested, engaged, while leaning forwards from the waist. His youthful vigour seems somehow coiled, primed for the life that awaits him.

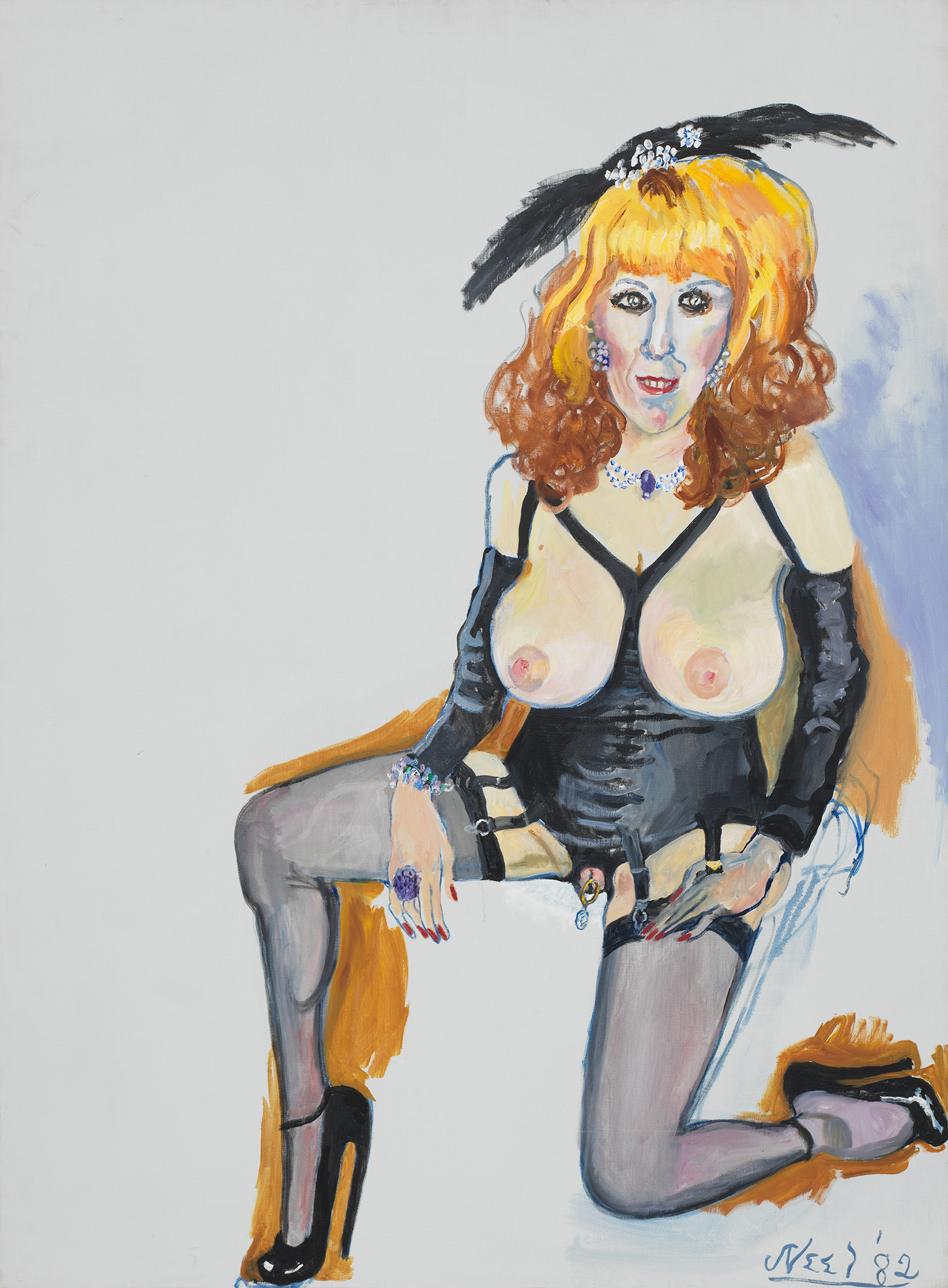

Alice Neel, Annie Sprinkle, 1982, oil on canvas © The Estate of Alice Neel Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel, David Zwirner and Victoria Miro

The quality of the sitter’s gaze that Neel captures is revelatory of character, and of the relationships the artist maintained. For instance, a 1962 painting titled Richard Gibbs’ Friend reveals a serious, slightly pudgy guy with pressed blue shirt and trousers, neatly slicked hair and an intellectual’s thickly rimmed, black framed specs. Nearby, Richard Gibbs himself appears in a 1965 painting, with cropped blond hair, tanned skin and apparently naked, he sits at the kitchen table in a pensive mood. We are left to ponder the friendship between these two ostensibly very different men.

In 1971 Neel moved again, this time to the Upper West Side. Her paintings of the next decade take on an elegiac quality, as they feature some of those who were to lose their lives in the AIDS epidemic that dominated the 1980s. She painted Denis Florio in 1978, languidly seated on an au-de-nil couch in a luscious, wine-red velvet suit. With his dark hair, moustache and world-weary expression, he is the image of the poet Marcel Proust, a deliberate borrowing on Neel’s part. In reality, Florio was a picture framer for the Whitney Museum, a flamboyant, gregarious personality who had been introduced to Neel by the performance artist and sex worker Annie Sprinkle, whose famous 1982 portrait by Neel is also featured in Als’ show.

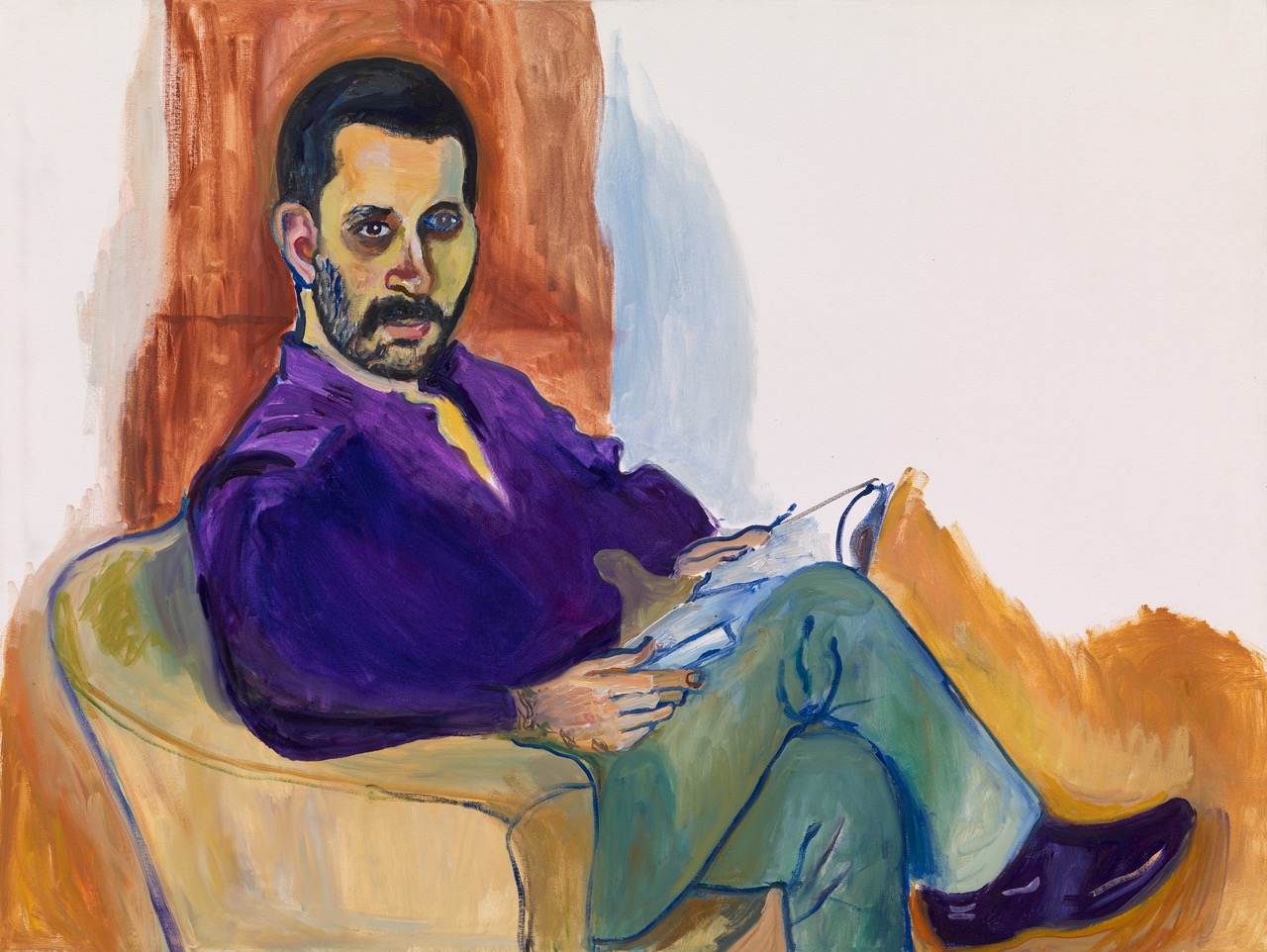

Alice Neel, Brian Buczak, 1983, oil on canvas © The Estate of Alice Neel, Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel, David Zwirner and Victoria Miro

Aged 21, the artist Brian Buczak moved to New York in 1975. Initially a painter, in New York his practice expanded to include film, performance and Fluxus projects. He died of AIDS at the age of 33, leading to Philip Glass’s commissioned composition String Quartet No. 4 which commemorated his life. Neel’s portrait of Buczak was painted a year before she died of cancer and four years before he died of AIDS-related illness. While in some of Neel’s portraits the subject seems to be staged or even self-consciously presenting a character, this is among the most intimate and natural of her portraits. Buczak appears to be momentarily looking up from the book in his lap – either responding to something Neel has said, or maybe simply absorbing what he has just read. The rich purple of his shirt hints at papal robes, his dark-rimmed eyes rendered with an ever-so-slightly skewed perspective that is reminiscent of Picasso.

Neel drew on her imagination and memory as well as painting from life. On the ground floor of the gallery, a portrait of Allen Ginsberg from 1966 appears quite anomalous in relation to all the others: it lacks the defining blue outlines and compositional clarity that defines her style. This portrait was rendered entirely from memory, after Neel attended a presentation of the psychedelic, multimedia ‘Illumination of the Buddha” lead by Ginsberg and psychologist Dr Timothy Leary, at the Village Gate on December 6th that year. In contrast to the archival photographs of the real event displayed nearby, in Neel's painterly rendition, Ginsberg appears to be in a trance-like state with some kind of hallucinogenic aura surrounding him.

Alice Neel, Adrienne Rich, 1973, ink on paper © The Estate of Alice Neel, Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel, David Zwirner and Victoria Miro

In sharp contrast are two drawings from the mid-1970s, portraying the prominent feminists Mary Garrard and Adrienne Rich. Neel loved men, but she was also a passionate feminist; these two drawings attest to the level of the discourse she was a part of. Known as one of the key initiators of feminist art history, throughout the 1970s Garrard published influential articles such as her 1977 essay, 'Feminism: Has It Changed Art History?'. In Neel’s drawing here she seems to have a slight scowl, as if arguing a point with the artist.

Adrienne Rich’s 1973 portrait drawing offers a representation of a woman with an entirely different demeanour. Rich was a poet and essayist whose work championed women (and lesbians in particular). From the mid-60s, she was active in the civil rights movement as well anti-war and feminist campaigning. In the drawing she looks girlish for her 44 years, though she had already received many accolades for her writing. Where the portrait of Ginsberg is hazy, the drawings of these two women are pin-sharp. We feel their presence and personalities. It is as if they have only just finished speaking and their words still resonate in the room.

Reflective of a past era, Alice Neel’s work is endlessly absorbing and reveals her unique ability to connect with her sitters – making them feel at home in her presence. “I like it not only to look like the person but to have their inner character as well. And then I like it to express the zeitgeist” she once said. This lovingly put together show offers valuable insights through some fascinating archival material on both floors of the gallery. Highly recommended.

Caroline Douglas, Director

At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World, Victoria Miro Gallery, London

16 Wharf Road, London N1 7RW, Tuesday–Saturday: 10am–6pm