John Hansard Gallery,

Southampton 11 February - 6 May

Bani Abidi was born in Lahore, Pakistan and has lived in Berlin since 2011 when she was invited to join the prestigious DAAD programme there. Before that, Abidi studied first in Lahore and then at the Art Institute of Chicago where she began to develop her practice in moving image. Now, one of the leading Pakistani artists of her generation, her career has included international solo presentations from the Sharjah Art Foundation to the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead and participation in Documenta 13 as well as the Berlin and Lyon Biennales.

Her new work, The Song, is debuting in the UK at the John Hansard Gallery in Southampton, where it is presented in an elegant, large-scale installation alongside an older work, Memorial to Lost Words, 2016. The exhibition has transferred from the Salzburger Kunstverein in Austria.

Abidi’s work typically combines fictional as well as documentary elements, often grounded in the experience of city living. She is renowned for her satirical, sometimes humorous examination of the structures of political power; previous works have centred on a presidential motorcade, or the rhetorical hand gestures of male politicians. Abidi deftly skewers pomposities and dissects the absurdities of institutional ceremonials. She has also addressed the continuing animosity and rivalry between India and Pakistan, the long hangover from Partition in 1947. Here, in The Song, however, something quite different is going on. Whereas other films have been set in the grand arena of the city, this is an intimist portrait of one man in his apartment.

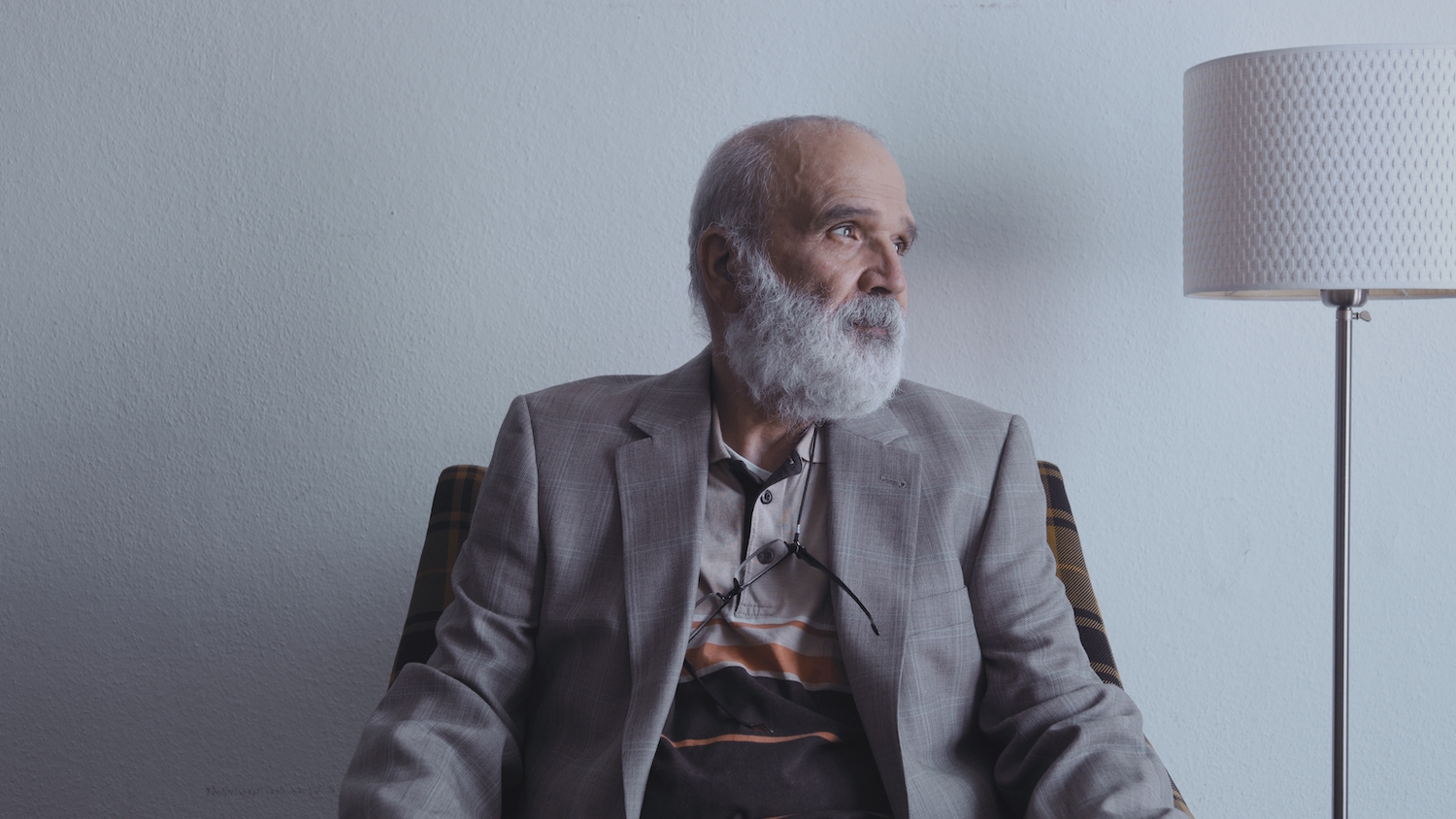

It is unclear whether the man is an actor; he is not named, nor is his nationality defined in the film. That he is a refugee in a northern European city becomes quickly apparent, as the opening few minutes show him in a bare apartment, bags at his feet, a few essential groceries from his ‘welcome pack’ arranged on the kitchen counter. Solitude hangs over the film like a second character; the man’s every movement and gesture speak of unfamiliarity, of his dislocation from another life. Twice during the film scenes from another city are cut in, shot from another apartment, from a similar height, looking out into the street. These are the places he goes to in his mind. The colours of that city are warm, the light golden. The contrast between the ‘German silence of double glazing’ and the streets of Damascus, alive with voices, cars, music, could not be greater. This auditory architecture is suddenly revealed as an essential part of a sense of home.

Periodically, we see the man toil up the stairs to his apartment, this time carrying a carpet, next an electric fan. Making home. He sits alone and still on his one chair. Time expands around him almost tangibly. He is of an age where one would expect him to be a respected figure in his professional world and, outside of that, busy with family, with children and perhaps grandchildren. Here in this isolation, he is thrown on his own resources. Doing his own washing. Navigating foreign food. He prays, he makes tea.

With great seriousness and deliberation, the man slowly constructs an orchestra of instruments from domestic objects. With something like the improvisational aesthetic of Fischli and Weiss, combined with the charm and inventiveness of modernist theatre, he takes a milk frother and electric toothbrush as protagonists, with plastic bags, cookie cutters and cardboard tube to fashion delicate automata that rattle and rustle, shuffling across the floor in a tragi-comic dance. In the final scenes of the film the man sits in his armchair, surrounded by his creations, singing quietly, under his breath. The humanity and dignity of this portrait are immensely moving. Though we know almost nothing about him, the film gives an insight into the man’s interior life, expresses complex combinations of longing, loss, comfort and human inventiveness. The novelist Kamila Shamsie has written a beautiful response to The Song, retrofitting some facts of his life, imagining him ten years on from the moment of the film; it is an affectionate, delicately drawn second portrait, perhaps best read a few hours after seeing the film.

The Song, 2022, was commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella, Contemporary Art Society, John Hansard Gallery and Salzburger Kunstverein. Supported by Arts Council England. Presented by Contemporary Art Society to Gallery Oldham

Caroline Douglas

Director

142 – 144 Above Bar Street, Southampton SO14 7DU

Opening Times: Tuesday to Saturday, 11.00– 17.00

Exhibition open until 6 May 2023