Clive Hodgson

Arcade gallery is celebrating its tenth birthday. We wish them many happy returns. Last year, the shifting of the art world’s tectonic plates became abundantly clear as a slew of small to medium size galleries threw in the towel, in the face of challenges that, finally, became too great to face down. Everyone needs to have a life. So there is much to celebrate in the resilience of galleries who do not own the lease on a whole block of prime real estate in three or more global cities around the world. Increasingly, there is talk of new models of operating that might side step the tyranny of the property market and the uncertain economics of art fairs. But I digress.

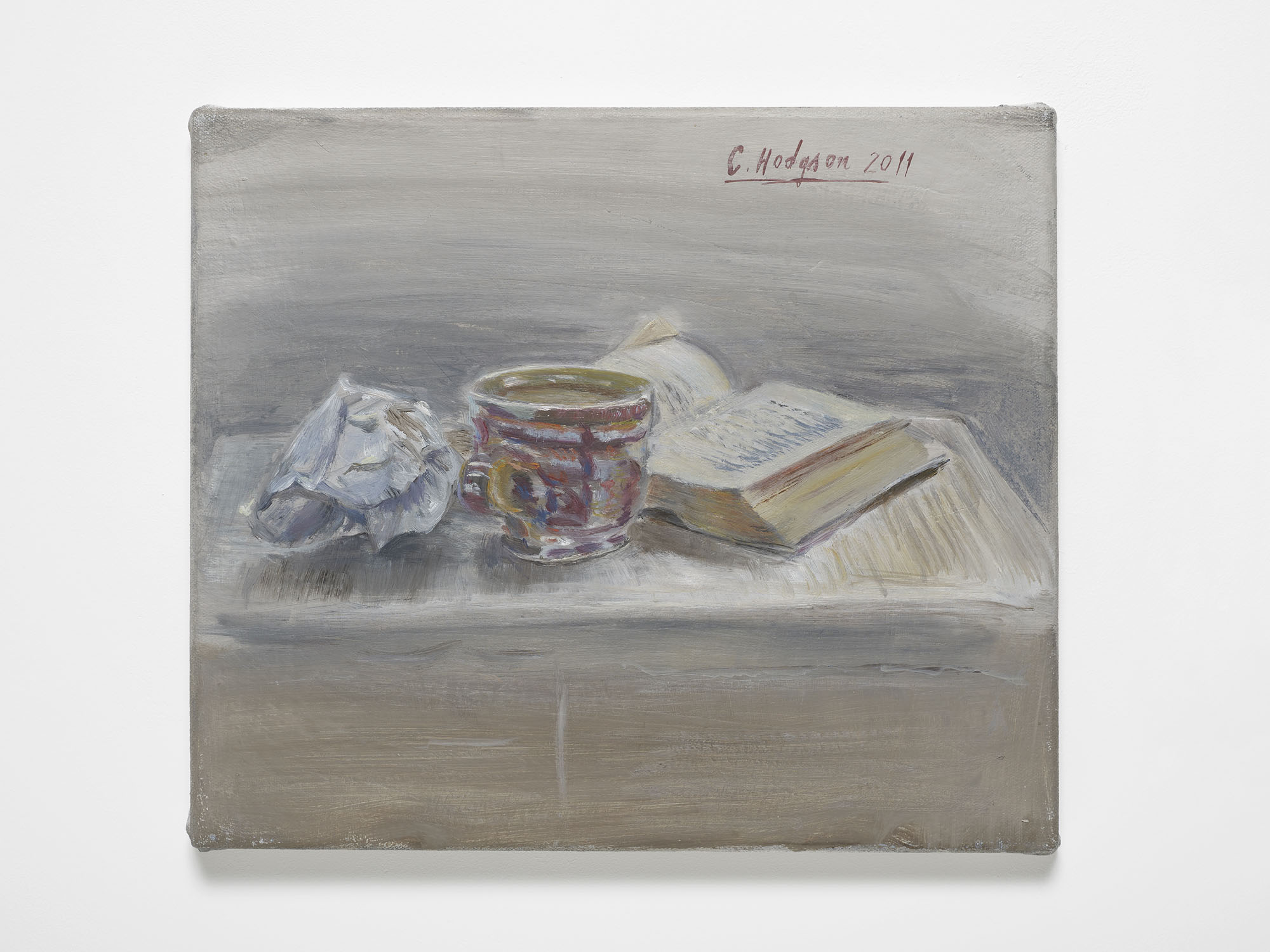

Clive Hodgson is the ideal painter to mark this big anniversary for the gallery. Dealing in a form of conceptual abstraction, he has long made the dating and signing of his paintings the foremost compositional element. The conceit of the current show is that before Christmas, the gallery showed paintings all made in 2017, but after the New Year, they rehung with works from a decade earlier, 2008. There is a nice – in the sense of precise – game here, with time moving forward but the view becoming retrospective.

Hodgson’s name – C Hodgson – and the date are the constant elements across a body of work that adopts differing approaches to abstraction from painting to painting. There is all-over scumbling that might reference process painting, or equally techniques of wall painting from the Roman era. There are nods to Jasper Johns in the targets, there is what looks like hard-edged abstraction, there is biomorphic abstraction. There are decorative devices, borrowed somewhere along the way, and swift graphic gestures that look like pure joie de vivre. Occasionally my pattern-finding mind imagined figurative devices, so that in one painting finely sprayed black paint blobs became murmurations of starlings over the flat winter horizon. But that is just me.

Anchoring each work, the artist’s name and the year of creation are used as compositional elements of equal weight. Sometimes the name is split in two, its meaning broken down to become form alone. Sometimes the date appears twice – once backwards, perhaps veiled by a thin paint layer, and then again the right way around. It’s almost as if the painting were designed for viewers on both sides of the canvas. Suddenly the picture plane – instead of resting on a support of canvas – seems to float as if in space. For a Janus-faced exhibition, looking simultaneously backwards and forwards, this is perfect.

Name and date are the most basic elements of art historical knowledge: who did this and when? The ‘when’ is important because one always wants to situate a work within the arc of an artist’s career; the implicit rationale being that one assumes progress of some sort is being made. But the idea that the history of art represents some kind of qualitative, aesthetic or philosophical forward progress has been discredited for decades now. And for all his emphatic assertion of his presence, and the relentless march of time through the paintings, Hodgson himself is absent. His playful deployment of abstract devices refuses the very idea of development, or the reflection of a life lived, in favour of an exploration of the medium itself.

There has, however, been change in Hogdson’s work. A group of paintings from the 80s in the Arts Council Collection attest to a moment early in his career when he was exploring figuration. A consciousness of the danger of creating narrative content that obscured the painting itself steered the artist away from this and towards a form of painting that had more to do with what he termed “lightness and dispersal”. The direction of his enquiry into the medium lead away from even abstract elements that could carry allusions – spots and stripes for example – and for a while he made use of decorative devices appropriated from Renaissance designs as more acceptably meaning-less motifs: “it had to do with the painting spreading outside of a confine. And that represented something that appealed to me – something rambling and not centred.”

This satisfying, somehow rather uplifting show is on for another month, so there is time to make sure you take it in, on your travels about town.

Caroline Douglas

Director

Arcade, 87 Lever Street, London EC1V 3RA. Wednesday - Saturday 12.00 – 18.00 and by appointment. Exhibition continues until 3 March 2018. www.thisisarcade.art