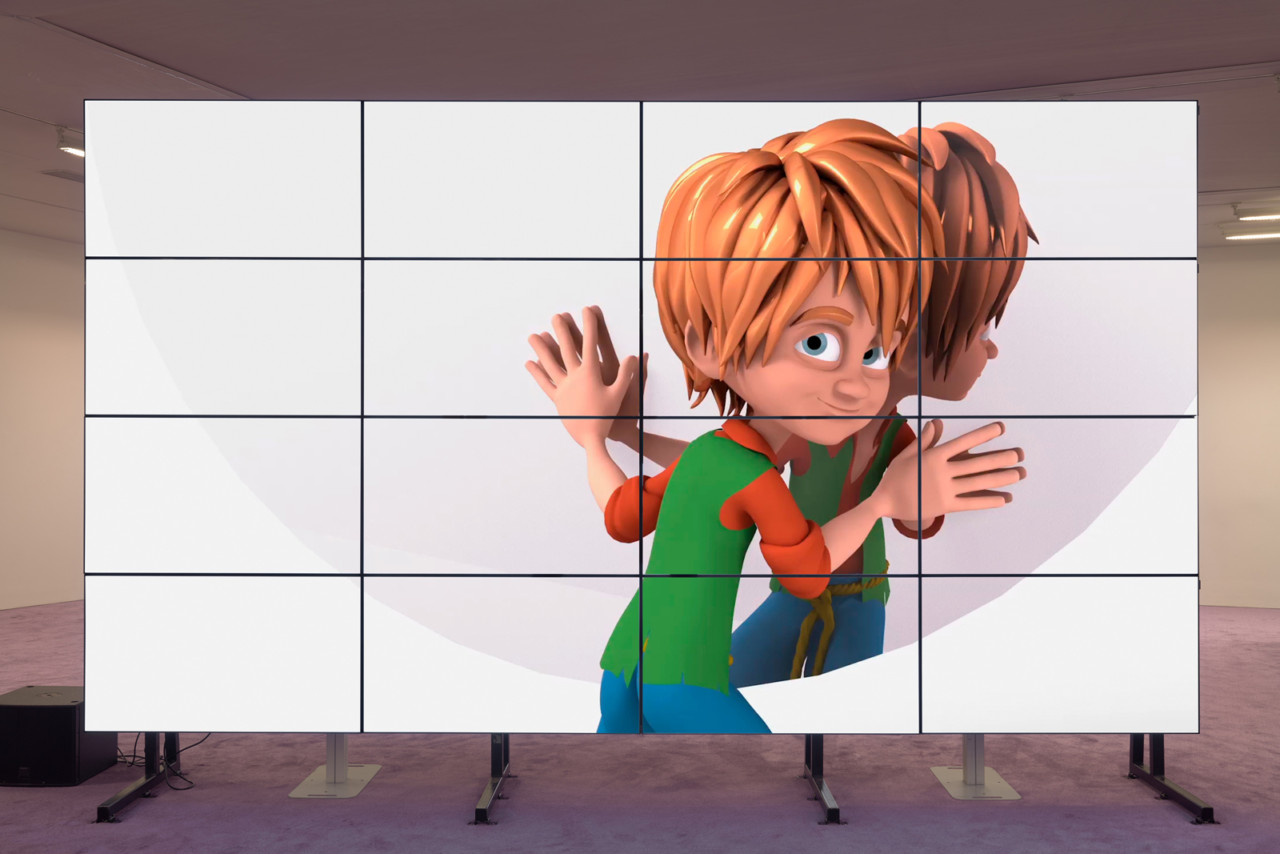

Installation view, Jordan Wolfson, Riverboat song, Sadie Coles HQ, London, 27 April – 16 June 2017. Copyright the artist, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photography: Robert Glowacki

Maybe it’s a generational thing, but I frequently wonder at the default level of narcissism on display wherever I go. Whether this manifests in the tourist hoards unironically pouting under their selfie-sticks in front of masterpieces in Florence or Venice – or in the minutely self-conscious grammars of Instagram adopted to broadcast the banalities of teenage life – for a person brought up not to “show off”, it’s a shock.

Jordan Wolfson’s new film is on show at the Kingly Street gallery, on a single, large scale screen set in a sea of lavender coloured deep-pile carpet. While I was there visitors instinctively reached down to take off their shoes. The colour is at once seductive and strangely bilious, in keeping with the tenor of the work. Like Philippe Parreno’s anime-inspired character Ann Lee, or Ed Atkins’ talking head avatar, Wolfson’s faux-fairy tale puppet boy is a recurring protagonist in his work. He is an unsettling blend of Pinocchio and Huck Finn with touches of the Chucky doll that first broke upon our consciousness in the 1988 film Child’s Play.

This boy wears a Disneyfied costume of ragged shorts and a rope belt, signifiers of poverty – for which read not ‘coastal elite’. At the beginning of the film he bumps and grinds in high heeled shoes, a kid frighteningly adept at the hyper-sexualised dance routines of pop videos. Porn star size breasts and buttocks magically burst out of his clothes at one point, only to fall off again like cheap stag-night accessories. Later on, the boy writhes and simpers by a circular mirror, back arched, looking over one shoulder in a pose that may have originated in 1930s Hollywood studio portraits but is now entirely codified within popular culture.

Over an animation of a crocodile in a bubble bath, and two be-suited horses affectionately dining together, a male voice gives a monologue, presumably delivered to a female lover. In the most entitled of drawls, he instructs his partner in how to flatter him, how to cook for him, how to accept his rage as a ‘natural reflection of her correctable behaviours’, and in a crescendo of misogyny, how she will accept his eventually leaving her, and take the advice of her family to ‘work on herself’ a bit. Then we are back with the puppet boy who drops his trousers to reveal his hairless genitalia and proceeds to frolic gleefully in his own urine.

As a Freudian allegory of unboundaried impulses and total self-absorption, it would take some beating. YouTube clips follow with a white thug beating up a black man pinned to the floor, a girl with her skirt round her waist dancing for the camera, and a family taking a train ride. And did I mention the sequences with punk rats smoking on an airplane?

In Davies Street there are two sculptures downstairs and an older VR work in the upstairs space. In glistening black the puppet boy is slumped against a wall, held more or less upright by a heavy gauge chain. His legs and arms are articulated like a crash test dummy, and they are jacked at weird angles suggesting a horrible accident. Both this sculpture and House with face, also here, are studded with outsize chain staples of unspecified function. The house is a miniature log cabin with the roof in the form of a witch’s face: think of the Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz and you are pretty much there. The witch and the puppet boy share the same grotesque grin that recalls the cruel mirth of the playground sadist.

These are bitingly sardonic works that operate nimbly across a multiplicity of media, negotiating the complexity of many different allusions without ever being explicit about references. Riverboat song feels quite precisely like the here and now and it really needs to be seen.

Caroline Douglas

Director

Sadie Coles HQ, 62 Kingly Street, London W1B 5QN and 1 Davies Street, London W1K 3DB. Tuesday – Saturday, 11.00 – 18.00. Exhibition continues until Saturday 17 June 2017. www.sadiecoles.com