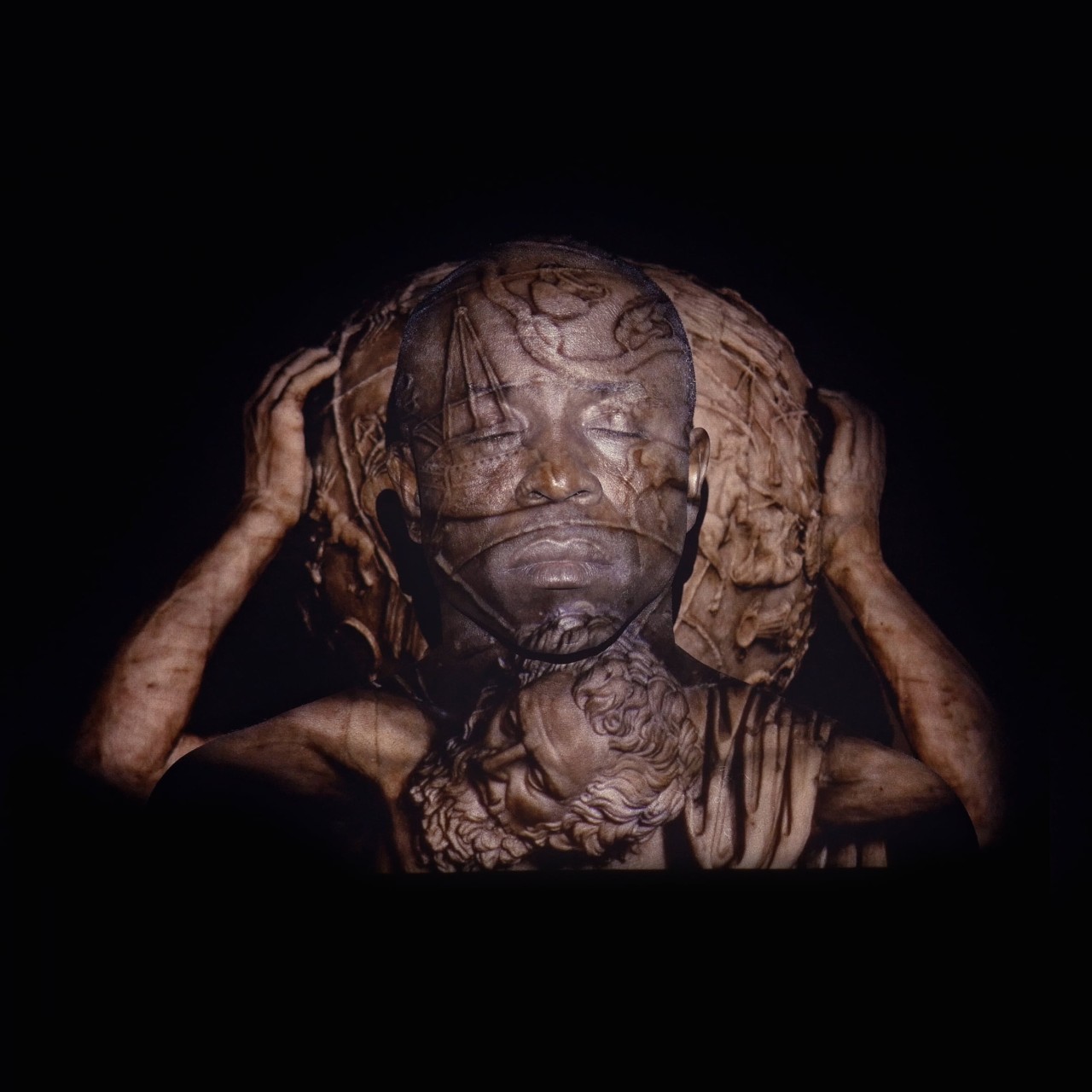

Theo Eshetu, Atlas Fractured 2017, digital video, installation view, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), documenta 14, photo: Theo Eshetu

The heady scent of orange blossom pervades the city of Athens in April: a beautiful and unexpected accompaniment to the opening of this year’s documenta exhibition. For its 14th edition, artistic director Adam Szymczyk has decided to split the quinquennial equally between Kassel, its traditional home, and Athens. He describes documenta 14 as a theatre and its double, a play in two acts, a divided self. All 160 invited artists will show at both venues and the divergent historical, socio-economic and cultural backgrounds of the two cities have inspired and influenced the newly commissioned works. The exhibition unfolds across two overlapping timeframes, Athens, from April to July, and Kassel, from June to September, over 163 days rather than the usual 100. Szymczyk seeks to redefine the notion of an exhibition as a unity of time, place and action. Happily, after this grand gesture, the artworks on display do not disappoint.

Athens is a charged location. The ‘cradle of Western civilisation’, it is geographically located at the crossroad of cultures and is currently the locus of our fears about the collapse of the European project. Greece has suffered from financial crisis, rising right wing nationalism and has been on the frontline of immigration from war-torn Syria. Szymczyk is keen to avoid clichés and allow us to ‘learn from Athens’, after first unlearning what we think we already know. He states in his introductory essay that he has chosen Athens as ‘a city that has become emblematic of global contemporary crises’. He continues ‘In Athens, the actual hardship of daily life is mixed with the humiliating stigma of “crisis” imprinted on the communal body in a well-known, pseudo-compassionate, moralising and in its essence neocolonial and neoliberal formula.’ The tension between Germany and Greece over debt and bailout forms the backdrop to Szymczyk’s decision to divide his documenta.

This relocation is in keeping with the initial impetus of documenta. The first edition, the brainchild of curator Arnold Bode, took place in 1955 – just ten years after the end of the Second World War and in Kassel, a city that had been destroyed by Allied bombing. It grew out of the US-driven economic reconstruction and state-driven moral re-education of Germany after the defeat of the Nazis. On display were modernist works that had been condemned by Hitler’s regime. Over the course of documenta’s life, massive political changes have occurred across the world that the directors of the arts festival have sought to reflect, securing documenta as a place for major debates on global contemporary culture.

Germany’s Nazi past is something that surfaces in several works in documenta 14, most notably the unsettling and opaque text-based installation Live and Die As Eva Braun (1995-97) by Roee Rosen which welcomes you into the Benaki Museum. This was one of several works that left viewers constructively puzzled. In the same venue was Sergio Zavallos’s A War Machine First Part, Fluid Mechanics (2017), in which a blueprint diagram of news events, from political assassinations to weapons development, was connected to a table of test tubes containing what purported to be urine extracted from world leaders, directors of corporations and army generals. Part Two of the work, to be shown in Kassel, will perhaps offer an elucidation. Another was Andre de Colombier’s eye-catching installation untitled (nd) consisting of objects in vitrines and words such as ‘les leçons’ inscribed on glossy sheets of paper on the floor and walls, reflecting your gaze back at you. Meanwhile Véréna Paravel & Lucien Castaing-Taylor’s mesmerising video somniloquies (2017) plays recordings of the ramblings of prolific sleep talker, the much-studied Dion McGregor, over close-up footage of sleeping bodies.

In Athens there are an incredible 47 exhibition venues listed but the four main venues are National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST), Athens Conservatoire, Benaki Museum and Athens School of Fine Art (ASFA), spread out across the city. Other venues have been chosen for their historical significance – the Technical University, where student protests against the junta in 1973 were suppressed by a tank, and the ex-military police headquarters in Parko Eleftherias (Freedom Park) where dissidents were tortured by the junta who ruled Greece from 1967-74. Many of the artworks on view, as well as these locations, are a timely reminder of us how much the landscape of Europe can change within one lifetime.

One of the highlights of documenta14 was the chance to view lesser-known work by indigenous artists. These included two Sami artists: Synnøve Persen, whose Sami Flag Project (1977- ) speaks of a search for identity and recognition in Norway, and Britta Marakatt-Labba, whose ethereal embroidered work Färden (The Journey/ Matki) (1986) shows a burial in process while departed souls float above. The first room at EMST was dominated by a striking installation of wooden ceremonial masks by Beau Dick, of the Kwakwaka’wakw people of Northwest Canada, who died last month. A fascinating essay by Candice Hopkins in the Reader reflects on the Klondike Gold Rush and its effect on first nations people who lived there and the Canadian government’s ban on indigenous Potlatch ceremonies that only ended in 1951.

Travelling between venues by foot, metro or taxi is an integral part of the exhibition experience. At ASFA you can take a well-earned rest with an ice coffee in the scruffy rooftop café before viewing the several stand-out works in the venue. They include Bouchra Khalili’s thoughtful film The Tempest Society (2017) which reflects on the refugee experience in Athens and the positive role of culture, inspired by a little known travelling theatre troupe Al Assifa in France in the 70s. Artur Żmijewski’s sobering Glimpse (2016-17) offers silent, black and white footage of the inhabitants of Calais’s notorious Jungle before its destruction. Looming environmental catastrophe is given a comic presentation in Bonita Ely’s epic installation Plastikus Progressus: Momeno Mori (2017) in which she invents species of animals constructed out of plastic appliances that are able to consume the detritus clogging up our waterways. A short walk away, Otobong Nkanga has changed an old print shop into an artisanal soap factory. Her work Carved To Flow (2017) uses eight different oils, carrying stories from across Africa, the Middle East and Europe, to make artworks of soap.

EMST is an impressively converted brewery with a view of the Acropolis from its roof terrace. Here, connections were formed between contemporary works and historical ones, such as an intriguing group of Soviet Realist paintings of women at work from 1960s Tirana. Lois Weinberger’s exquisite museological installation Debris Field (2010-16) consists of objects dug up from beneath her family farmhouse in the Tyrol, including plants, shoes and cat skeletons. It offers an uncanny reflection on what lies beneath the apparent safety of the domestic and the burden of guilt of the past century. Meanwhile Daniel García Andújar fills a room with his installation The Disasters of War, Metics Akademia (2017) which comments on the use and abuse of Classical aesthetics and philosophy over the centuries, a strong theme running through the exhibition. It is made up of small 3D printed models of deformed versions of familiar classical sculptures, alongside a life-size cast for the Artemision Bronze, and black and white photographs documenting racial classification.

The most beautiful venue is the starkly modernist Athens Conservatoire, in an unfinished cultural complex. Here, in the concrete shell of a performance space, Emeka Ogboh’s multi-channel sound installation The Way Earthly Things are Going (2017) juxtaposes hauntingly beautiful, almost unearthly, African singing with a real time LED display of world stock indexes flashing in the dark. In another room, one lined with gold streamers, Theo Eshetu’s strange, slow-burning video work Atlas Fractured (2017) captivates. In it, a series of works of art, from Greek sculptures to African tribal statues, to Renaissance paintings are projected onto living people; and then the process is gradually reversed.

Documenta 14 spills out of its multiple exhibition sites into radio programming, Every time A Ear Di Soun, and screenings, Keimena, on ERT2 the national television channel. There are also a series of publications, including the weighty, excellent and unmissable Reader, a public programme entitled The Parliament of Bodies that started last autumn, and the Aneducation programme. Go to Athens and see this moving, thoughtful and provocative exhibition for yourselves, in advance of your five-yearly ritual visit to Kassel.

Ali MacGilp

Curator

documenta 14 in Athens continues until Sunday 16 July 2017, documenta 14 in Kassel runs from Saturday 10 June - Sunday 17 September 2017. www.documenta14.de