Before going to see this exhibition in Dulwich, don’t read any reviews. Don’t re-watch TV dramatisations of the lives of the Bloomsbury group. Don’t trawl Wikipedia. What you really need to do is clear your mind, in order to allow yourself to really, properly look at the work. Extraordinarily, this is the first ever monographic exhibition to focus on the life’s work of Vanessa Bell, and it offers not only an opportunity to survey the evolution of her style over several decades, but to see a large number of works borrowed from private collections, and therefore rarely, if ever, seen.

Because ‘the Bloomsburies’ come with a lot of baggage, to put it mildly. It has been fashionable to take a political stance and to dismiss the entire group as over-privileged bourgeois bohemians, toying with a watered-down version of European modernism. There has always been a kind of titillated fascination with the complexities of the interconnected love lives of the group; and the domestic focus of so much of their work has caused it to be denigrated as somehow amateurish, parochial and even saccharine. Now we have a chance to make up our own minds about Vanessa Bell, at least.

The concurrent exhibition Sussex Modernism at Two Temple Place emphasises the radicality of the move to Charleston that permitted the members of the Bloomsbury group to explore ways of loving and living that would have scandalised polite London society in the first decades of the 20th Century. It also puts into feminist perspective the concern with decorative arts for the home, situating the ceramics and textiles produced on the same level as the ‘fine art’ of painting.

In his essay for the excellent catalogue that accompanies the exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery, the renowned American art historian and Bloomsbury scholar Christopher Reed discusses other aspects of the domestic focus of so much of Bell’s work. He cites Roger Fry’s contention that “the human spirit had evolved from concern with the exceptional, the supernormal or even the supernatural, to the familiar, normal, commonplace things of life …the most familiar things if only we look at them with a concentrated imaginative gaze are full of wonder and mystery.” Marcel Proust’s ability to conjure the minute detail of everyday experience in exquisite prose is deployed as an example.

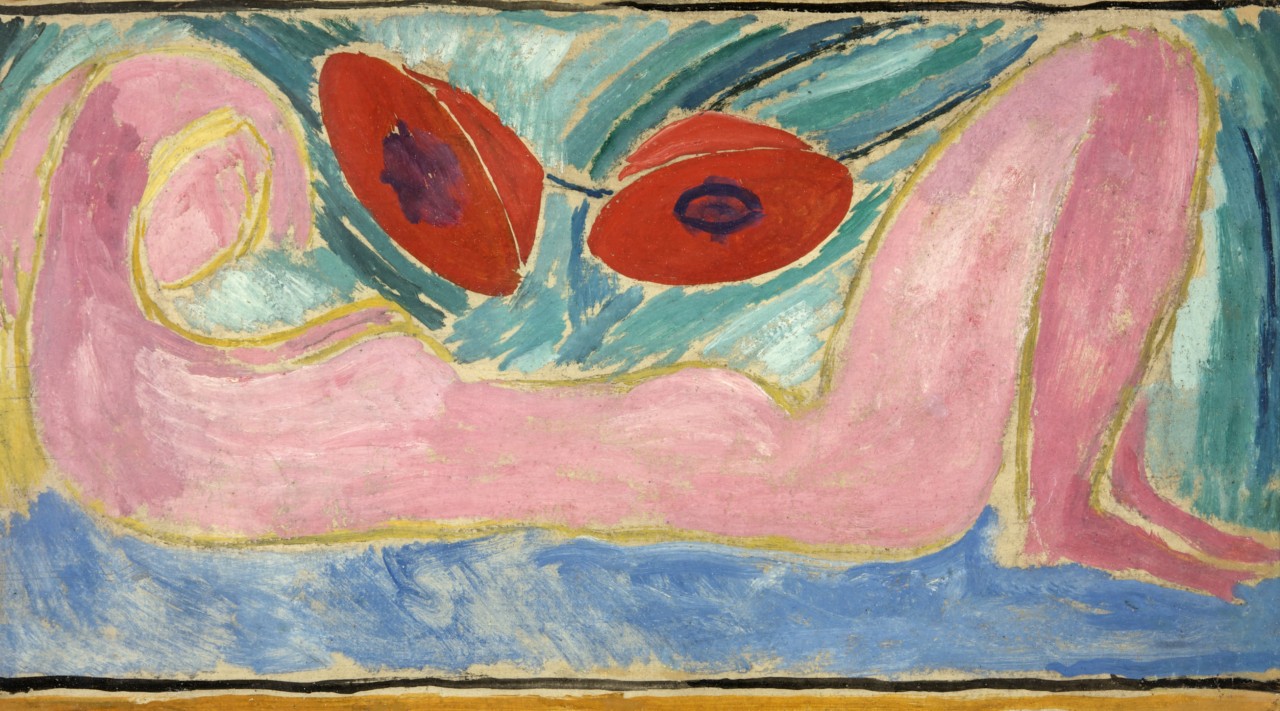

The exhibition is arranged thematically, looking at still life, landscape and portraiture so that one has to dodge about, looking at the labels to understand the chronology of her development. The majority of the works on show date from the period around the First World War, and crucially that period in which, led by Roger Fry, members of the group travelled repeatedly to France, and to the studios of Cézanne and Matisse, among others. Thus we can appreciate that the distance that Bell travels in her own aesthetic evolution between say, the slightly academic Icelandic Poppies of 1908-9 and simplified, flattened forms and intense colour of Tea Things of ten years later, is immense.

Surprises in the show include two works that employ the collage techniques Bell will have come across in the studio of Picasso in Paris. Still Life (Triple Alliance), 1914 incorporates fragments of maps of Europe, a cheque and newspaper clippings; the Portrait of Molly MacCarthy, 1914-15 is a monumental portrait, hugely self-confident in its use of papier collé to describe form in bold slabs of emerald and scarlet. The works denote an artist freely experimenting with the possibilities of new techniques. In the last room of the show, the folding screen Tents and Figures, 1913 seems to synthesise influences from France in its abstracted landscape forms, and the stylised, jade green female figures with mask-like faces.

It is tempting to abandon oneself to pure enjoyment in this exhibition, to love the peaceable arrangements of family groups, the quietude of the patterned interiors and the Italian vases with drooping garden flowers (how interesting would it be to hang one of these still lifes in proximity to a Wolfgang Tillmans photograph that betrays the same intimacy), but this is not enough.

The discipline one must bring to the exhibition is to keep a grip on the historical context for Bell’s work: one must remember that the men in her life were conscientious objectors and that the windows of Charleston farmhouse rattled with the sound of the artillery across the channel in 1917. At a moment that demanded high patriotism and conformity, Bell and her circle were not only radical in their living arrangements but in their departure from classicism as a model. In a time of revolutions, Roger Fry was accused of “aesthetic bolshevism”.

The exhibition and the accompanying catalogue have clearly been a labour of love to put together for curator Sarah Milroy and Dulwich’s departing director, Ian Dejardin. They are a milestone in scholarship and I heartily recommend both to you.

Caroline Douglas

Director

Dulwich Picture Gallery, Gallery Rd, Southwark SE21 7AD. Tuesday – Friday, 10.00 – 17.00. Exhibition continues until Sunday 4 June 2017. www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk