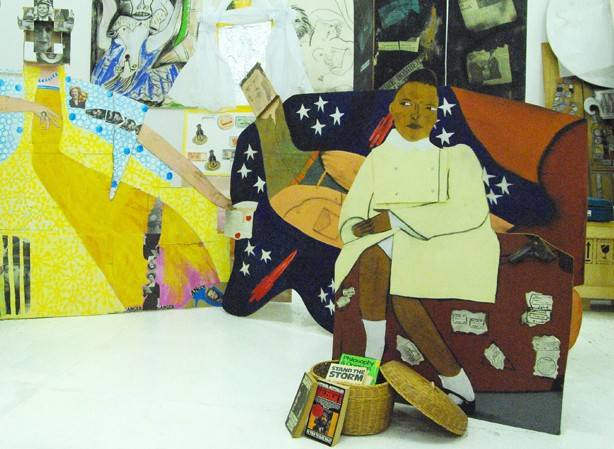

Lubaina Himid, A Fashionable Marriage, 1986. Courtesy artist & Hollybush Gardens. Photo Matthew Birchall & Tao Lashley-Burnley

‘We are claiming what is ours and making ourselves visible’ wrote Lubaina Himid in the 1980s, a decade that was shaped by economic inequality, civil unrest and racial division. At the same time, this fertile intellectual period saw the emergence of post-colonial and cultural theory, influenced by Anti-Apartheid Movements, Black Feminism and the Civil Rights Movement.

The Place is Here at Nottingham Contemporary features over 30 black artists as well as collectives from the UK. Focusing on the 1980s, it brings together around 100 artworks spanning from painting, photography, video, sculpture and installation to archival displays.

The exhibition that is spread across four rooms is curated as a montage of viewpoints and artistic voices. Each room’s title is drawn from one key work of art displayed in that same room.

Signs of Empire refers to the title of an early film by the Black Audio Collective. It shows artists such as Rasheed Araeen and Sonia Boyce, who played a crucial role in reflecting on colonial legacies and expanding art history beyond the West. Gavin Jantjes' South African Colouring Book, 1974-75 is a critical commentary on South Africa’s apartheid regime as well as an early call to decolonise modernism. The work was shown at the ICA in 1976, influencing young black artists who recognised themes they were concerned with in their own practice being discussed in a main stream gallery for the first time. Also, Eddie Chambers’s Destruction of the National Front, 1979-80 is a remarkable piece, responding to the rise of the National Front Party that aimed to ban non-white immigration in the 1970s. The artist produced this series of four collages by tearing up the Union Jack and re-arranging it as a swastika. The Blk Art Group Research Project, founded in 2011 by former Blk Art Group members, promotes understanding of what has become known as the British ‘Black Arts Movement’.

The second room’s title is taken from a poem written on a work by Lubaina Himid from 1986: We Will Be. This wooden cut-out piece that challenges conventions and forms of power is displayed in the centre of the room. Nearby, Donald Rodney’s installation The House That Jack Built, 1989-90 raises question about cultural identity and body politics. Martina Attille’s film Dreaming Rivers, 1988 is an elegiac meditation on migration and dislocation from a female perspective. Attille has said that this film ‘illustrates the spirit of modern families touched by the experience of migration’. The character of Miss T in the film is partly a collage assembled from interviews with first-generation Caribbean women from the artist's own archive. At the end of the film, Miss T cries out ‘England’, powerfully expressing Dreaming Rivers’ exploration of contested national identities. The archive display Making Histories Visible, curated by Himid, is comprised of a still growing collection of ephemera and books on a wide range of topics ranging from African American and Black British politics to novels, plays and poems by black woman and an extensive collection of exhibition catalogues by black artists.

The third room, The People’s Account, draws on a film from 1985 by Ceddo Film and Video Workshop. Works in this room focus on major uprisings in Handsworth, Brixton and North London that shocked the UK in the mid-1980s and were sparked by police violence against black people. New film collectives formed during that time, profoundly influenced by post-colonial theorists such as Stuart Hall and Homi K Bhabha. John Akomfrah’s Handsworth Songs, 1986, Ceddo’s The People's Account, 1985 and Isaac Julien’s Territories, 1984 question how moments of civil unrest were portrayed in the mainstream media by telling protest stories from the perspective of Black and Asian people. Also an archive display from Jamaican born Vanley Burke calls for new modes of documenting and remembering black culture in Britain.

The final room, titled Convenience Not Love, documents Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, displaying satirical comments on this period that subvert art-historical references. Lubaina Himid’s life-sized tableau A Fashionable Marriage, 1986, named after a piece by the 18th century artist William Hogarth, includes Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, two political figures that stand for the divisive politics of the era. In Chila Kumari Burman’s Convenience Not Love, 1986-87 Thatcher is depicted as John Bull, the stout personification of Britain. To contextualise the art works with factual information, key publications, exhibition reviews and other writings from that time are also available.

The Place is Here allows us to look back at a pivotal decade for British culture and politics with a historical distance. It triggers us to realise with discomfort that many of the issues at stake in the 1980s have lost none of their relevance today. It is a revelation to witness the energy with which a generation of young black artists, mostly coming fresh from art college, fought for their place within an art world that was seen mostly as white and western in the 1980s. Some of the works in the show come from public collections, however much of the work in the exhibition has never been seen in public. Even though a number of black artists seem to have a strong visibility in contemporary art institutions across the UK at present – Lubaina Himid is on view at Modern Art Oxford and Spike Island, Bristol, Sonia Boyce at the ICA, John Akomfrah won this year’s Artes Mundi Prize – the question arises why it has taken almost 30 years to gain the visibility that black artists were already fighting for in the 1980s.

Christine Takengny

Curator, Museum Acquisitions

Nottingham Contemporary, Weekday Cross, Nottingham NG1 2GB. Tuesday – Friday, 10.00 – 18.00, Friday 10.00 – 23.00, 18.00, Sunday 11.00 – 18.00. Exhibition continues until Sunday 30 April 2017. www.nottinghamcontemporary.org