Elizabeth Price, 'A RESTORATION', 2016, two screen HD video installation, 18:36 min. Courtesy of the artist and MOT International, London & Brussels. Made in response to the collections and archives of the Ashmolean and Pitt Rivers museums, commissioned a

Two years in the making, Elizabeth Price’s much anticipated new work, A RESTORATION, opened last night at the Ashmolean. An institution renowned more for its outstanding archaeological collections and classical sculpture, the collaboration with Price signposts a new engagement with contemporary art. A RESTORATION has been produced as a result of the Contemporary Art Society Annual Award, which the Ashmolean and Price won in November 2013, and the work now enters the museum’s permanent collection.

“We are cultivating a garden in a remote corner of the server” says the softly spoken, female machine voice at the opening of the film. As ever with Price’s works, a didactic voice narrates, leading the viewer through dense accumulations of images. The voiceover appears simultaneously on-screen throughout, as animated text, on pale pink or blue panels in Calibri font – the familiar visual grammar of Microsoft Word. Combined with a soundtrack of loud, pulsing electronic music, and the staccato succession of images, this is one of purposeful urgency, propelling the viewer from one proposition to the next.

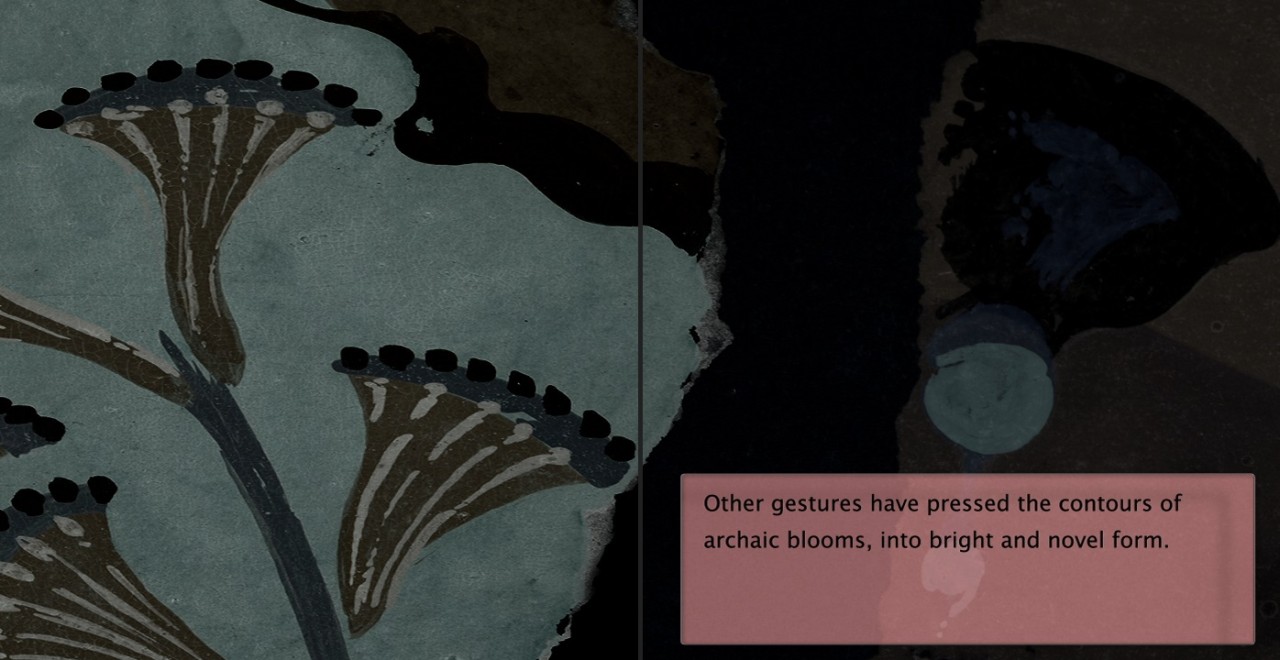

The voice is that of a shadowy administrator who refers obliquely, but authoritatively to an unnamed “we”. Price has drawn on the photographic and archival records of the Ashmolean and Pitt Rivers Museums, and particularly those relating to Arthur Evans, the archaeologist who, from 1894 undertook the excavation of the Minoan palace at Knossos on Crete. Evans’ work at Knossos was controversial for its bold leaps of imagination in restoring architectural features as well as terracotta vessels and other artefacts. Beautifully elegant CGI sequences of the film detail the elaboration of decorative devices on these, and end with terse quotations from academic commentary – “Vigorous Stylistic Variation” – filling the screen in red banner text that recalls El Lissitzky via Barbara Kruger.

On the face of it, this subject matter is not immediately the most engaging – administrators are rarely the heroic protagonists in any artform – but Elizabeth Price’s unique way of addressing her subject renders it intellectually thrilling, as well as physically exhilarating to experience. In A RESTORATION the concept of the museum is invoked through successive allusions to the garden, to a palace, a labyrinth and a computer server. The determining agency of the administrator, as the mediator of meaning, is illustrated through the original photographic records of finds at Knossos, made in the field in the early years of the 20th century with a combination of makeshift expediency and academic rigour. A sequence towards the middle of the 20 minute film has the narrator/administrator, bored by the repetitiveness of their own procedures, playfully, or reprehensibly, raiding files of images to create alternative archives for their own use. Documents float digitally out of yellow files and layer into stacks of images that mimic the museology so characteristic of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum, ignoring geographical origin or historical period but uniting objects through use-value.

The film draws to a close, extending the notion of the labyrinth to the form of the spiralling cochlea of the ear – and bringing into conjunction two quite different artefacts from the museum through percussive sound and fracture. The Ashmolean holds thousands of small, unfired clay figures, believed to have been a part of the contracting of marriages for thousands of years from Eastern Europe through to Mesopotamia. Female figures, bearing striking continuities of stylistic features appear to have been broken to signify the making of a contract. It is speculated that it was not the visual aspect of the act that was important, but the sound of the break. Against this a 17th century glass goblet engraved with a picture of a king in a tree, records the moment in 1651 when Charles II hid in an oak in Boscobel Wood after the Battle of Worcester to escape capture by the Roundheads – an act that led to the restoration of the monarchy. Paradoxically, the glass goblet celebrates an ideal form of government, in the most fragile of breakable materials. In a final, ecstatic sequence, the glass falls through the air (digitally, folks) and smashes crisply on the ground.

Having watched A RESTORATION at least a half dozen times, I am a still a long way off unpicking all the layers of this most brilliant work, dense with detail and finely considered form. Take the train and devote an afternoon to it – the exercise will repay you handsomely.

Caroline Douglas

Director

Elizabeth Price, A RESTORATION, the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, OX1 2PH. Open 10am to 5pm Tuesday to Sunday, and Bank Holidays. Exhibition continues until 15 May 2016. www.ashmolean.org