Teresa Pągowska in her studio, 1977, courtesy Teresa Pągowska Estate and Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London photo: Tadeusz Późniak

Thaddaeus Ropac

13 February until 2 April 2025

“A painting may arise from a dream. The most important dreams cannot be revealed; it is to me that they present themselves. They will leave their marks on paintings” once reflected the Polish artist Teresa Pągowska in 2001. A significant figure in her native Poland, Pągowska has belatedly made her UK debut in the show Teresa Pągowska: Shadow Self at Thaddaeus Ropac, London – nearly two decades after her death. Curated by Oona Doyle, a long-time admirer of Pągowska’s work, the exhibition assembles work from the 1960s until the mid-2000s. Existing tentatively between figurative and abstract painting, the oil paintings and collaged works on paper are displayed in the elegant corridors and upstairs galleries of the light-filled, 18th-century Mayfair townhouse, revealing the recurring motif of the shadow.

Born in Warsaw in 1926, Pągowska was raised by a well-to-do family who moved to the city of Poznan after her mother, Helena, died in 1930. Pągowska was thirteen years old when the Second World War broke out and Hitler invaded Poland. Subsequently, she witnessed the fall of her city to the Nazis – less than two weeks after the start of the conflict. Under German occupation, the western region of Poland was forced to adopt German as the official language, schools closed and teenagers were forced to work, meaning Pągowska spent much of the war doing manual labour in the city gardens. According to her grandson, Filip, she later joined youth units of the underground resistance movement, known as the Grey Ranks. In 1978, she created the work Hommage au Ghetto de Varsovie (1978), which she dedicated to Marek Edelman – the Jewish leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943, one of the most significant acts of resistance during the war, which resulted in the complete destruction of the capital’s Jewish ghetto. In an attempt to flee Poland, Pągoswka’s older brother Wiktor was caught by the Gestapo when attempting to cross the border. He was sent to Auschwitz, where he eventually died at the age of 23 in 1944. By February 1945, Poznan was liberated by the Soviets, after heavy fighting between the Germans and the approaching Red Army. According to Filip, Pągowska rarely spoke about the atrocities of the war, but the horrors of that time had an immense impact on her early years and remained a painful memory throughout her life.

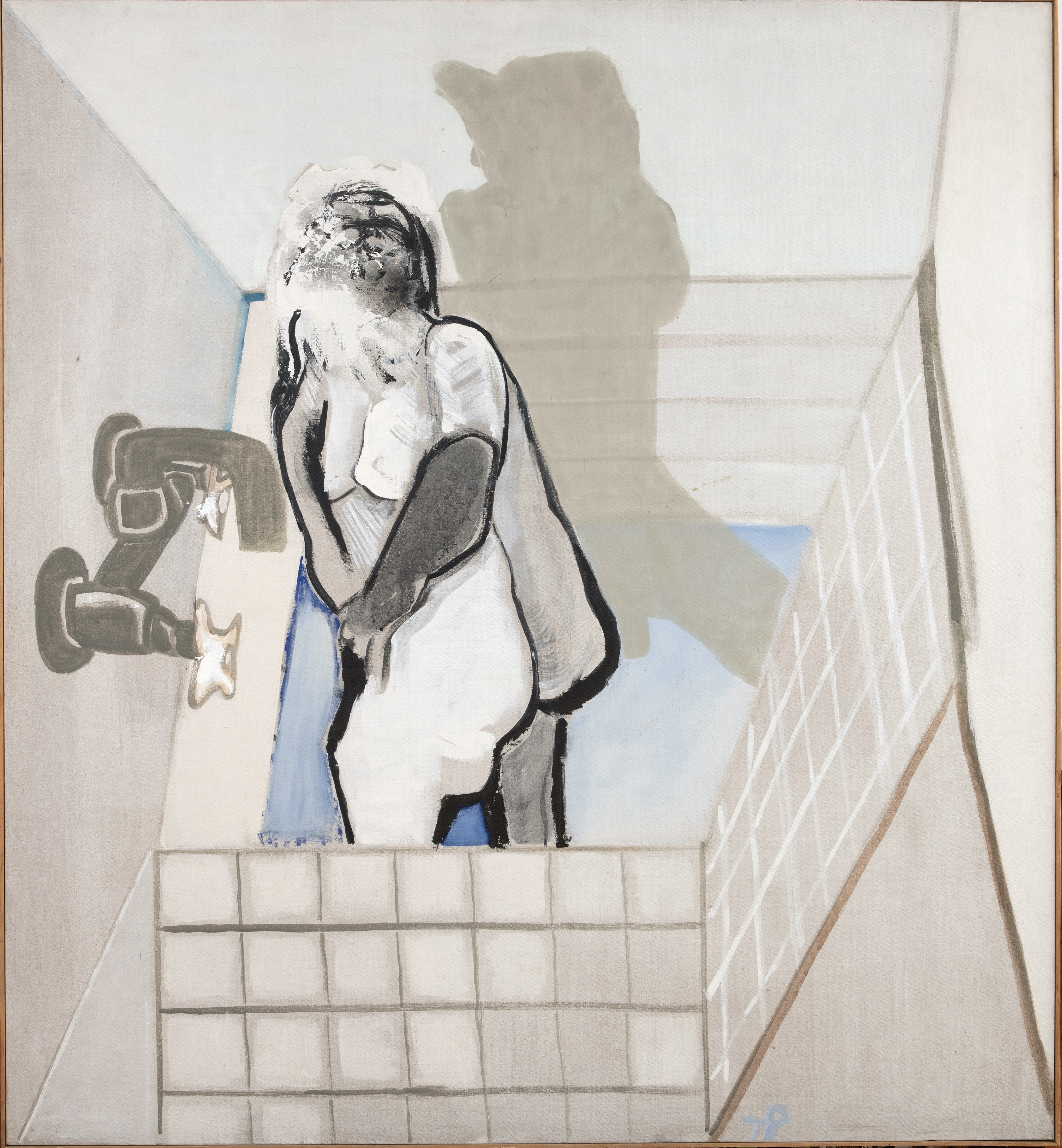

Untitled ,1966, oil on canvas, courtesy Teresa Pagowska estate and Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, London

After the war, Pągowska turned to art. She received a diploma in painting from the Poznan Academy of Fine Arts, where she studied under artist Waclaw Taranczewski, who had been influenced by avant-garde European movements. Pągowska then moved to Warsaw, where she eventually took up a teaching position at the Academy of Fine Arts, earning the title of professor in 1988. As the decades progressed, she continued to experiment with form, colour and most notably – the female form as a subject matter. In early works such as Untitled, 1966, a canvas of deep blues points to the possible influence of colour field painters of American Abstract Expressionism, while the fragmented yet faceless figure in the centre alludes to the tormented physicality of Francis Bacon’s subjects. Whispers of Bacon can also be detected in the composition of Kapiel (Bath), 1974, in which a distorted, corpulent figure – in hues of white, grey and black – stands in a brightly-lit, white-tiled bathroom. Behind, a dramatic shadow creates a sense of depth and suspense. The claustrophobia of the image is palpable and disquieting.

Kapiel (Bath), 1974, courtesy Teresa Pągowska Estate and Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London photo: Tadeusz Późniak

According to art historian and curator Connie Butler, Pągowska, along with Polish contemporaries such as Alina Szapocznikow and Magdalena Abakanowicz, was one of the first Polish artists to consciously address the subject of the female body. By doing so, she created a distinctive, figurative aesthetic, one that – concurrent to burgeoning discussions around the role of women in society – problematised the female form. Pągowska’s women are elusive and non-representational; they aren’t beautified, nor do they reflect any art historical tropes of the female body. They are featureless and anonymous; standing in as archetypes rather than specific individuals. However, we know from her writings that Pągowska painted intuitively, meaning to interpret them as works of auto-fiction – bearing some resemblance to self-portraiture – doesn’t seem too far-fetched. In her writings, Pągowska regularly described the entanglement of self and painting: “The physicality of painting creates me. Canvas, paints, brushes, well and my hands – these are materials for a painting. So I like to touch, to change into it. I like to be the canvas, the paint, the brush…hence the painting?”

While Pągoswka’s work echoes the modernist preoccupation with form (“form is more important than content, or equally important. They go hand in hand…”), Pągowska’s paintings are rooted in the artist’s psyche. Ruminations on the self are equally discernible in her poetic writings, displayed alongside her works in the Thaddaeus Ropac galleries. In this sense, Pągowska’s art is a form of self-exploration – a journey into the darker recesses of her mind. As evoked by the show’s title, to have a ‘shadow self’ refers to the theories of psychoanalyst Carl Jung, who like his close contemporary Sigmund Freud, spent much of his career investigating the possibilities of the subconscious. Explaining his theory of the shadow self, Jung once wrote: “Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual's conscious life, the blacker and denser it is [...] But if it is repressed and isolated from consciousness, it never gets corrected. It is, moreover, liable to burst forth in a moment of unawareness. At all events, it forms an unconscious snag, blocking the most recent attempts.”

In the era of post-war Europe, we might regard Pągowska’s paintings – humming with psychological tension – as manifestations of her subconscious, or at least, a delayed processing of her lived experience. Painting offered more than a daily habit or refuge, but also as a tool for psychological release. These works weren’t merely a portal into her inner life, but a mirror – reflecting what had been repressed and acting as a sounding board for continual self-discovery, as both a woman and artist: “I ask my pictures thousands of questions. Answers to these questions have to be found within myself.”

Shadow Self situates the artist as a significant figure in the landscape of post-war European art, bringing a deserving and overlooked artist out of the shadows.

Lydia Figes, Curator of Digital

Teresa Pągowska: Shadow Self

Thaddaeus Ropac, 37 Dover Street, London, W1S 4NJ

13 February until 2 April 2025