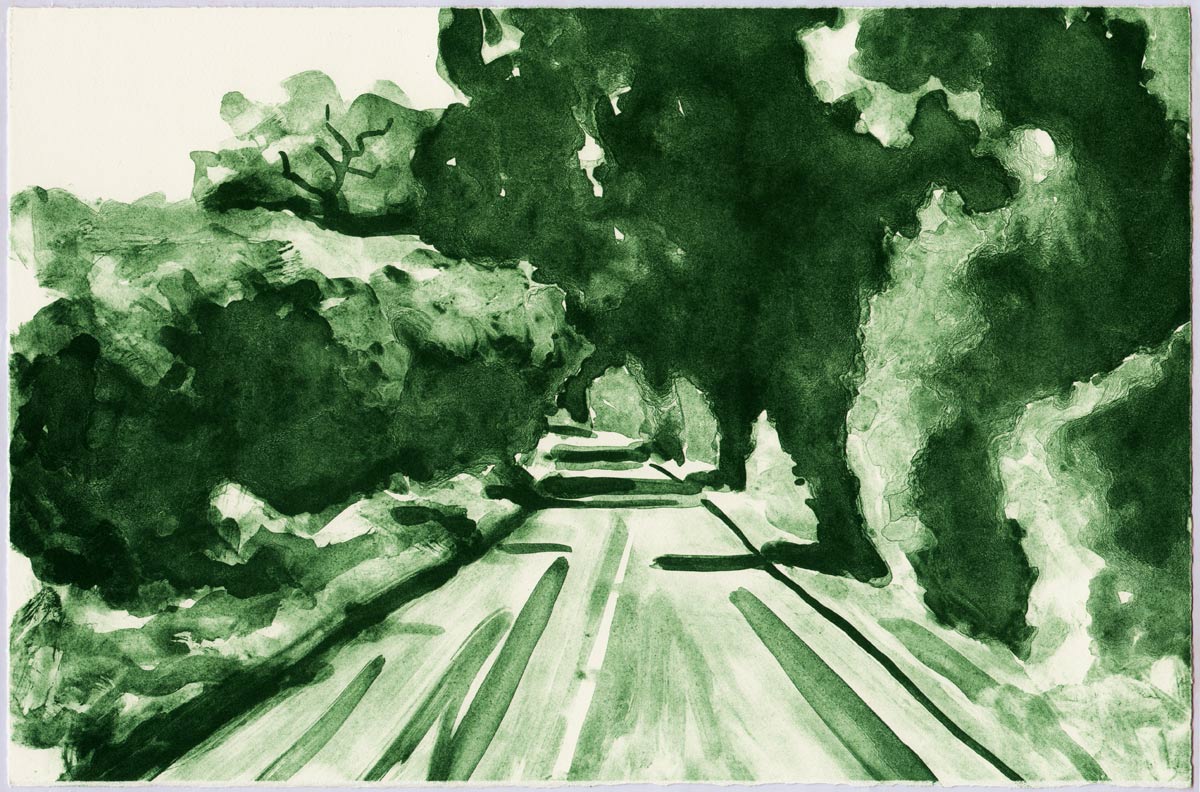

George Shaw, The Boys All Shout For Tomorrow, 2014, Humbrol enamel on board, 56 x 74.5 x 5 cm. Copyright the Artist, courtesy Wilkinson Gallery, London. Photo: Peter White

It is four years since we have had a chance to see a body of new work by George Shaw. In 2011 he had an enormous solo show at Baltic in Gateshead, which some of you may have caught in an edited version at the South London Gallery the same year. Some may even have seen his show at the Herbert Art Gallery in Coventry. For the last year Shaw has been Associate Artist at the National Gallery, but we will have to wait until the autumn of next year before we begin to see the results of that residency.

This period of relative invisibility may have lulled some in to a feeling that they know all about his work; that they could not be surprised. We know, for example that since the mid-90s he has painted the landscapes of the housing estate in Tile Hill, a suburban district of Coventry in the Midlands where he grew up. We know that he has made many paintings of aseptic 1960s mass housing, of derelict pubs, garages, schools and community centres. We have come to expect stretches of wet concrete rendered with a kind of paradoxical romanticism, graffitied walls and decaying fences translated with a degree of humanity worthy of John Piper’s paintings of bomb damaged buildings after the Second World War.

The six large scale paintings in the lower gallery at Wilkinson are different. Familiar, yet quite radically different. Each one depicts a metalled road – curving either to right or left away from the viewer through a wooded landscape and receding into the distance. So Shaw has done roads before. Roads, paths and pavements recur frequently, but not like this. The first thing that strikes you is the darkness – each painting looks as if painted from a photograph taken at that fleeting moment when day turns to night. You peer into the composition to make out the details, eyes adjusting as if you had just come out of bright sunlight. Shaw is one of those people who never learned to drive, so this is the perspective of a man walking the road, on the right, facing oncoming traffic. Yes, do read a metaphor there.

Five of the six paintings are all called Study for The Painter on the Road. You will probably recognise the title as taken from a work by Van Gogh in which he depicted himself, laden with canvas and boxes of paint and brushes on his way to work. Painter on the Road to Tarascon from c1888 was destroyed during the Second World War, but Francis Bacon took up the motif in a series of paintings he made in the 1950s. (There are works from the series Study for a Portrait of Van Gogh in the Arts Council Collection, Tate and Sainsbury Centre.) Shaw’s paintings, like those of his august predecessors, are about the work – as in the labour – of the painter.

And Shaw works very hard indeed: in his studio by 6.15 every morning and rarely leaving before 7pm. He lives and works in rural Devon too – so there is little to distract from the matter at hand. But the second thing that you will notice about these paintings is the very different handling of the paint itself. Shaw has always used Humbrol paint. (His notes to the exhibition reveal the macabre detail that he began using it when he learned it had been used in the murder of a child by other children.) These new paintings are no exception in that respect, except that the flat, meticulous rendering of pin-sharp detail is gone and in its place is a new looseness of mark making, coupled with a dark and fathomless sensuality in the material. It renders these big, dark, brooding paintings utterly riveting. Shaw’s paintings have always been about the passage of time, the urgent need to catch reality before it slips away. Each painting here is almost a monument.

Upstairs are fourteen smaller scale paintings, each in the tighter style familiar from earlier work. Each revisits sites of previous paintings. There is the sweet suburban peace of late afternoon light on red 60s brickwork; blank windows with their nets and blinds; there are neatly cut logs inexplicably arranged in a circle in russet-coloured woodland. The sharp smell of decaying leaves over wet earth, and graffiti on tree trunks that reminds us of Shaw’s fascination with woodland as primal space where transgression is permitted. There is not room here to discuss them all in detail, much as I would like to. Go see the show. Stay long. Look hard.

Caroline Douglas

Director

Wilkinson Gallery, 50-58 Vyner Street, London E2 9DQ. Exhibition continues until 12 July 2015. Open Wednesday - Saturday 11.00 - 18.00 and Sunday 12.00 - 18.00. www.wilkinsongallery.com