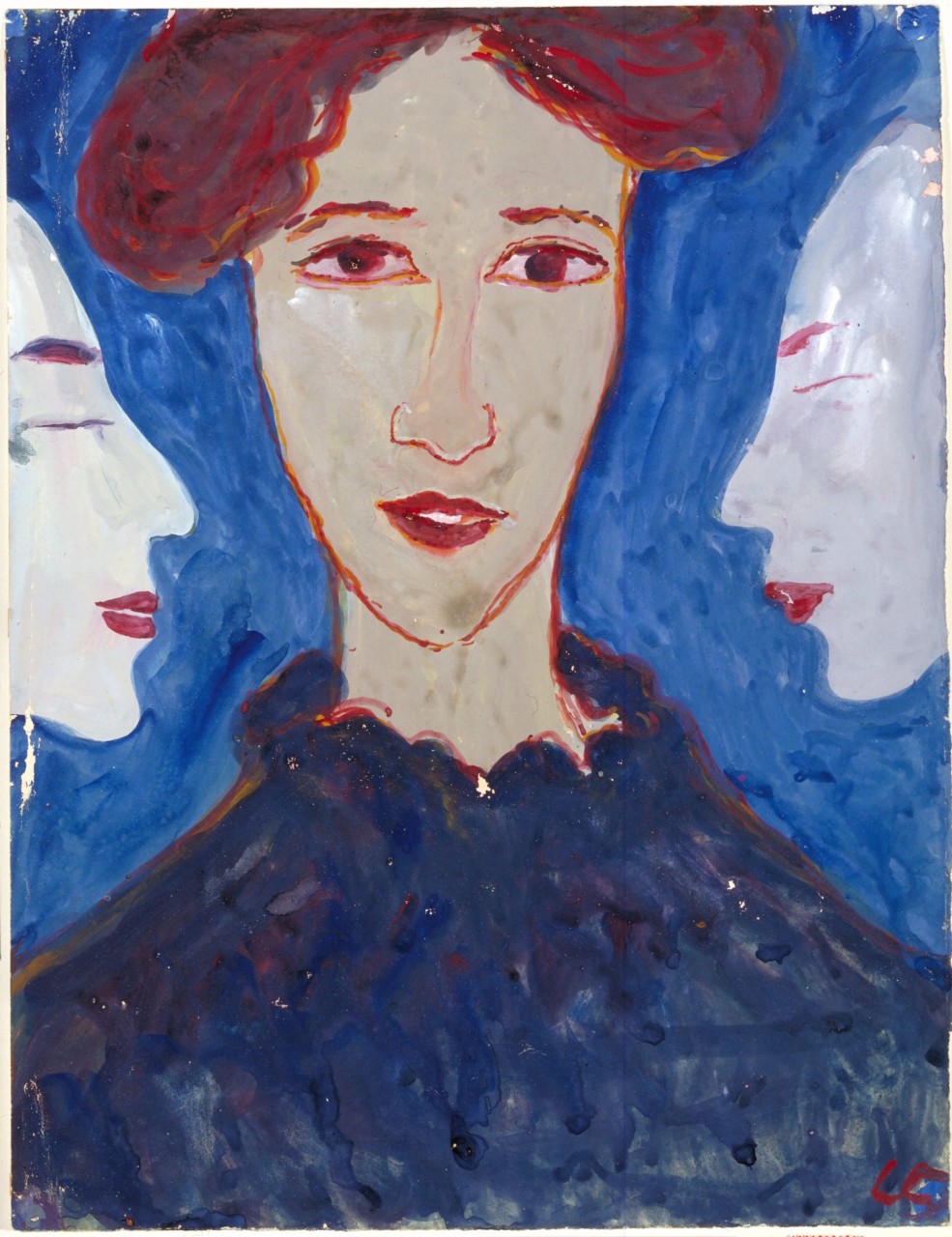

Charlotte Salomon, ‚Leben? oder Theater? Ein Singspiel (Life? or Theatre? A Play with Music)’, 1941–42. Collection Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation

Born in 1917 to an affluent Berlin family, Charlotte Salomon trained in graphic arts as one of the few female Jews among the students of the academy in Berlin. In 1938 she fled Germany to join her grandparents in exile in France, and whilst hiding from the Nazis she completed the vast subject of this exhibition: Life? or Theatre? A Play with Music. She was later murdered in Auschwitz, aged 26 and 5 months pregnant.

Although It would be tempting to classify her work as “Holocaust art”, it would also be misleading. Life? or Theatre? A Play with Music is a series of over 700 gouaches accompanied by text, intended to be performed in lyrical theatre. 236 representative works are on display here. The work is structured in three parts: the prelude, the main part and the epilogue, narrating the story of Charlotte and her family from 1913 to 1940. The first scene is set in 1913 when her aunt throws herself in the lake at Schlaten.

Charlotte Salomon, or Charlotte Kann, as she names her character in Life? or Theatre? A Play with Music, was born in April 1917. Her mother, Franziska is initially ecstatic with baby Charlotte, yet soon after “Franziska ceases to find pleasure in anything…. She speaks only of death.” She attempts suicide but Albert, her doctor husband, brings her back to life. Monitored by a nurse, Franziska is supposed to getting better, but death is constantly on her mind: at a time when no one is watching, she jumps out the window. Her death is immediate.

Young Charlotte is told her mother has died of influenza and a governess is appointed to cheer her spirits. She travels, reads books and draws; she frequently goes to the opera with her father to see the glamorous and charismatic opera singer Paulinka, whom her father later marries. Charlotte admires the talented Paulinka. The latter takes on a voice coach who becomes Charlotte’s music teacher and an emotional triangle unfolds: Charlotte falls in love with him. He becomes Charlotte’s mentor and first lover, although he is actually in love with Paulinka who keeps him at a distance, but whose flirtatious nature heightens his desire.

This domestic drama takes place against the backdrop of war. Charlotte’s father soon loses his job and Paulinka’s singing career is stalled. He is arrested and tortured by the Nazis and only manages to escape death when Paulinka presents forged documents to the authorities and he is released. At that point, the couple feel that Charlotte is no longer safe in Germany, so they usher her to the south of France where she can live with her grandparents.

In France, Charlotte is safe from the Nazis but not from the family demons. Charlotte’s grandmother Marianne suffers from the same depression that killed her daughters and attempts suicide, initially with no success, but she finally manages to throw herself out the window. Her grandfather lays before young Charlotte the long history of mental illness that Marianne suffered and implies she will follow suit. Charlotte, unable to cope with this revelation – or rather the realisation of a hereditary stigma – slowly poisons her grandfather. The work ends with Charlotte in hiding, reflecting on the events that have come before.

What is compelling in this “graphic novel” is not only the breadth of ideas and stunningly dramatic story, but the genre-bending forms of expression. Through the relentless interplay between image, music and text, Salomon invents a new genre: autobiographical art. The transparent gouaches mirror her family trauma and existential angst, but they also resonate with the state of the world at the time. They are deeply personal, but also universal in the way they convey the violence of war, the fragility of human existence and the bleakness of death.

We are led to believe that the events are accurately represented, but she narrates her life at a remove. After all, this is not the story of Charlotte Salomon, but the story of Charlotte Kann, as she has named her heroine in the piece. In this sense, the work itself is an extraordinary achievement that blurs the boundaries between fact and fiction, asserting Salomon as one of the earliest voices of auto-fiction.

The way she paints is equally remarkable: some gouaches bear affinities with Chagall’s work while others are reminiscent of Munch and Modigliani. As we are immersed in her drama, the style becomes reminiscent of the German expressionists, with strong references to Kirchner and Beckman. The change in her painting style reflects her state of mind, the enduring stress of her tormented soul. It also resonates with her desire to erase herself in the face of coming tragedy: “Each character has to sign a character less to the author than the varied nature of the characters to be portrayed’, the text writes. “The author has tried to go completely out of herself”. Even outside herself, Salomon is simultaneously the narrator, commentator, instigator, perpetrator of an extraordinary artistic achievement.

This fascinating exhibition urges us to explore different art forms in order to position Salomon’s oeuvre within political and personal narratives and to ask fundamental questions about life, art and trauma.

Vassilios Doupas

Curator of Programmes

Jewish Museum, Raymond Burton House, 129-131 Albert Street, London NW1 7NB. Open Saturday-Thursday 10.00-17.00, Friday 10.00-14.00. Exhibition continues until 1 March 2020. www.jewishmuseum.org.uk